The cyanotype series by Chinese artist Zhang Dali, which was on display at Eli Klein Gallery from May 19 to August 19, 2023, features six primary images: a man, doves, crabapple, pagoda tree, foxtail, and horseweed. In a subjective sense, these objects evoke descriptions of a confined individual, doves seeking freedom, a crabapple representing Beijing’s transformation, unattended weeds, and a pagoda tree for watching. The moment in which Zhang captured these objects contributed to this effective thinking. It's imperative to emphasize that his surroundings, not the internet, are the source of these visual representations. In Zhang's statement, he began recording wild plants with cyanotypes in 2009 after discovering them in a wasteland west of his studio in Heiqiao, Beijing. We now notice the neglected landscape as a result of this.

Installation view, Zhang Dali-Suffocation at Eli Klein Gallery. Courtesy of the artist and Eli Klein Gallery

As an artist practicing graffiti in China throughout the 1990s, Zhang has consistently attempted to convey the complex state of the city and its inhabitants, the reasons why they are formed, and the relationship that comprises them. Before focusing on residents’ thoughts and states, he used demolished buildings in the urban system to analyze the change in the surface of the city. In response to the real-world scenario, Zhang expanded his research gear to include the city’s wild plants in the cyanotype series, showcasing his thoughts on the rural-urban fringe’s landscape. Unlike other types of landscape, this one is home to a variety of uncategorized and undesirable wild plants. Botanists and locals will most likely assign them a scientific name and an alias. Regardless of the name, but, they are the outcome of human observation and the replication of man’s imagined rights, which in turn impose restrictions.

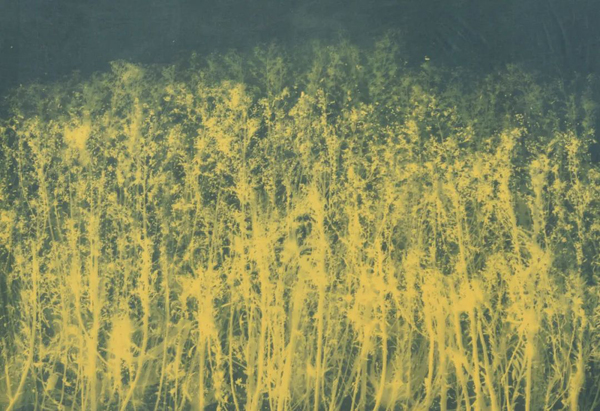

Zhang Dali, Herbarium Canadian Horseweed (C. canadensis) (1), 2020, yellow cyanotype on cotton, 135×190cm. Courtesy of the artist and Eli Klein Gallery

Zhang initially observed the encircling wildflowers and weeds against the backdrop of a modern city in rapid development. Similar to that carved out hole to provide him with a view of the capital city, these untamed plants allow him to catch a glimpse of individuality and nature in this urban development. The cyanotype pieces were made during this period so they have a staged urban imprint and raise the following query to the younger generation distanced from the vernacular landscape: “Can you now identify more than five varieties of these weeds?” (according to Zhang’s statement). Remarkably, these exhibited works were created during the global pandemic, a worldwide emergency in which human outdoor activities ceased and flora and fauna thrived abundantly. It is the loss of human-oriented controllability and conditions that accounts for this lushness, not people’s negligence. Therefore, these works bear witness to the city and its inhabitants during a special period and demonstrate the conditions required for all forms of life to survive. More profoundly, it made people take a closer look at nature as they returned to their cubicles and gave it some consideration. Even if one cannot discern any kind of weed or wildflower, that doesn’t contradict their ongoing existence – a vitality that often outlasts human lifespans.

Herbarium Blue Crabapple (M. spectabilis) (11), 2020, blue cyanotype on cotton, 225×160cm. Courtesy of the artist and Eli Klein Gallery

The wild plants meticulously chosen by Zhang represent our life’s reality, much like other flora and fauna in his works, but their shadows serve as a function of disclosure. To elaborate, the cyanotype copies the shadow of an object, separating it from the subject and acting as a reveal. This is similar to how shadows in paintings counter the reality on which they are based. In Zhang’s pieces, the shadow is analyzed by its expressive form that harmonizes with the backdrop while being independent in the form of a black paper cutout, reminding us of American artist Kara Walker’s black cut-paper silhouettes that discuss race and identity. The cyanotype method reduces objects to their basic shapes, emerging as profoundly realized portrayals of the “human being” within the given context.

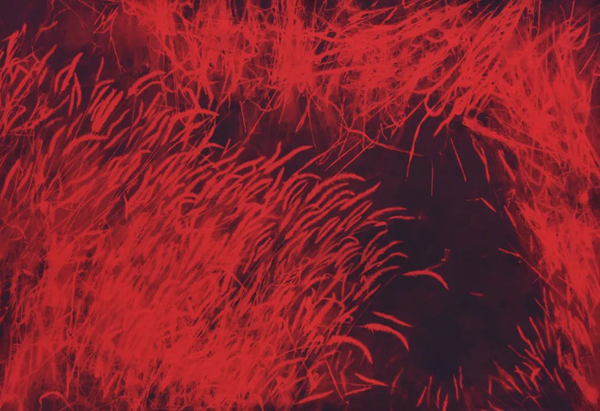

The colors Zhang used on the cotton further illustrate this concept. All pieces can be categorized into red, yellow, and blue colors. Displaying in this way provides different visual psychology, imagination space, and an emphasis on life’s beauty. Dove (55) (2021) and Breathe (35) (2021) each build a sense of urgency and powerlessness as well as a desire for peace. The weed’s shape in Herbarium Foxtail (S. viridis) (4) (2020) resembles moving human veins in vibrant red. The full-bodied image of Herbarium Blue Crabapple (M. spectabilis) (11) (2020) has distinct structure, space, and variations in light and shadow. This is because the cyanotype relies on the interaction of chemical substances with solar light so the lighted and unlighted parts create shadows of varying tones. The image is covered in blue, giving it a sense of dense moisture. White shadows are scattered throughout, setting off the cotton texture and giving the impression of brushstrokes, which adds a hint of painterliness and aesthetic nature.

Herbarium Foxtail (S. viridis) (4), 2020, red cyanotype on cotton, 118×170cm. Courtesy of the artist and Eli Klein Gallery

With the red tone, the slogan of “I Can’t Breathe” and the images of people behind the iron mesh and the pigeons in the sky have a strong visual symbol that directs the same symbolic meaning. In a way, they corroborate what outsiders believe, and the slogan that is not intended to coincide with the BLM movement that erupted earlier. The concise shape of the dove appears in various artists’ works such as Magritte and Henri Matisse. Yet this repetitive form, like the recurring word AK47 in Zhang’s past works, also represents the rejection of violence and the need for personal space in one’s situation.

Dove (53), 2021, blue cyanotype on cotton, 145×230cm. Courtesy of the artist and Eli Klein Gallery

Zhang encourages us to consider the relationship between art and technology, as well as time, by incorporating the old technique created in 1842 by John Herschel in England into the contemporary thriving technological civilization. Simultaneously, this also reflects the idea that artists do not necessarily have to “move forward,” but rather take up the neglected in the process of looking back at history. From being popular to being shelved to being ignited by different artists, the changing times and nostalgia contained in the cyanotype are pertinent to Zhang’s artistic tone and style. These works, which he collectively calls “the world’s shadow,” reflect the reality of our existence and the beauty of life.

Zhang Dali was born in Harbin, China in 1963. He graduated in 1987 from Beijing National Academy of Fine Arts and Design. An influential figure in China, Zhang Dali has, for decades, challenged the conventional with his social documentation in graffiti, sculpture, photography, and painting. Zhang was exiled after graduating from the Central Academy of Fine Arts and spent six years immersing himself in Western art and art history in Italy. Upon his return to Beijing, he developed a keen interest in portraiture (usually of himself), documentary and public urban art, often interrupting spaces with confrontational political statements. He is critically recognized as one of China's first graffiti and street artists.

In 2014, Zhang Dali presented a comprehensive solo show at Klein Sun Gallery titled Square, which featured his cyanotypes, fiberglass sculptures, and paintings. The renowned contemporary art journal Yishu reviewed the show, mentioning that "the points Zhang Dali is making exist beyond historical specificity; they attain a view of humanity that is startlingly real. In this way, he achieves the status of world citizen and world artist, one who helps open up the lines of communication with the rest of the world that China has at times denied during its recurring periods of inversion and mistrust."