When discussing landmarks in East Lansing, Michigan, the MSU Broad Art Museum must be mentioned for its independent form and style of campus buildings such as Collegiate Gothic and Internationalism, and the commercial architecture off-campus. A stainless steel fa?ade is accompanied by tilted and rising forms, which are obscure to locals. And students called it a “spaceship.” It, as the first building on campus by the late Iraqi-British architect and designer Zaha Hadid (1950-2016), hosted Zaha Hadid Design: Untold from September 10, 2022 to February 15, 2023--the most comprehensive Zaha Hadid design exhibition in the United States--curated by the Broad’s former Director Dr. Mónica Ramírez-Montagut, and Woody Yao of Zaha Hadid.

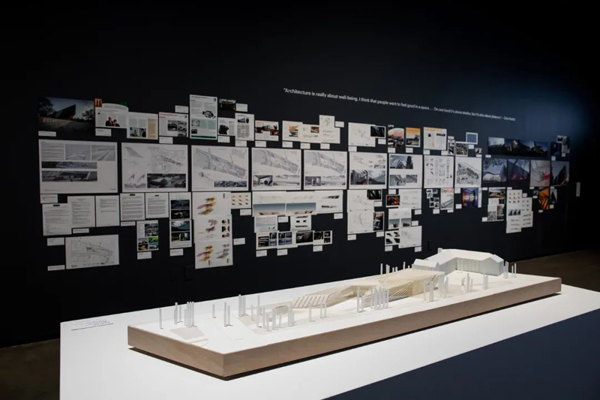

Zaha Hadid Design: Untold installation view at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University, 2022. Photo: Eat Pomegranate Photography. Courtesy MSU Broad Art Museum

Hadid is renowned for her architecture and was the first female architect to receive the Pritzker Prize. However, the exhibition focuses on her designs for furniture, dinnerware, fashion, lighting, jewelry, and an electric car prototype. Wandering into Hadid’s diverse legacy, one can contemplate her design philosophy, the use of material opulence and infinity, and the ways she redefined things. The different types of works reveal their intrinsic connection to the Broad Museum and, as always, challenge common perceptions and impressions of objects and environments with highly innovative visual concepts.

Zaha Hadid Design: Untold installation view at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University, 2022. Photo: Eat Pomegranate Photography. Courtesy MSU Broad Art Museum

Zaha Hadid Design: Untold installation view at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University, 2022. Photo: Dustin Forest. Courtesy MSU Broad Art Museum

The exhibition occupies three floors. However, the second floor, which features a dining room set, fashion, and other works, has been closed early for some special reasons. The main gallery on the first floor brims with Hadid’s dazzling works that are difficult to decide where to begin. But there is a certain regularity that can be seen in the exhibition design. The four carpets (Pixel, Cellular, Ribbon, Striation, 2018) with Hadid’s iconic elements dropped from the ceiling, the gray stick paper on the floor, and the white showcase with glassware and a chess set divide each area of the gallery. Alternatively, the works are organized into zones based on similar properties and characteristics. In terms of color and concept, the three painted reliefs behind the carpets, for instance, two of which are Hadid’s unrealized plans for the Abu Dhabi Performing Arts Centre and the Vilnius Museum, form a space with the small car next to them. Elaborately designed gray sticker papers highlight the works while corresponding to the gallery’s spatial features. They stretch forward and intersect with the carpet edge that falls to the floor. Eventually, one’s gaze draws to the window in front of them and blends them together naturally. Even the presence of the flickering lamps Luma (2017) does not compromise the visual psychology that seamlessly integrates Hadid’s work into the surrounding environment.

The nearby gallery features Dune Formations (2007), a series of organic installations with furniture elements installed on the white walls and the floor. Their distinctive shape is determined by analytical geometry, which relates to Hadid’s experience studying mathematics before attending the Architectural Association (AA) School in London. The golden-orange color and smooth curves allow one to be in the desert and experience the softness of the wind blowing over the sand dunes. Recall the memories of Michigan’s once-thriving automobile industry: these oval sharp-edged surfaces like those formed by wind erosion, face the entrance as if many speeding cars were stirring and accelerating the state of space. The installation’s curves and surfaces are elegantly fluid in the light, reminiscent of the Aria & Avia (2013-17) lamps on the second floor with architectural elements--appearing as smooth asymmetric surfaces from a distance and as layered curved thin lines up close. They even return in a fluid way to abstract paintings with curved lines, such as a few yellow curves in the adjacent painting Metropolis (1988), and contrast with the linear geometry of the Suprematist-inspired Malevich’s Tektonik (1977) next to it.

Zaha Hadid Design: Untold installation view at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University, 2022. Photo: Eat Pomegranate Photography. Courtesy MSU Broad Art Museum

Zaha Hadid Design for Slamp, Aria and Avia, 2013–17. Courtesy Slamp. Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum, Michigan State University, gift of Slamp, 2022.6.1–4, and purchase, Eli and Edythe Broad Fund for the Acquisition of Modern and Contemporary Art, 2022.6.5

Often referred to as the “Queen of the Curve,” Hadid’s belief in “360 degrees,” and her bold challenges to geometric structures and traditional forms, among others, cannot overlook her exploration of the multidimensional nature and possibilities of materials. Glass, wood, carbon fiber, granite, cristalflex, etc., are all shaped by her as a reflection of movement, aesthetics, dynamics, and the environment. The flower-like Orchis (2008) chair, Mesa (2007), which looks like a water lily floating on water, and Zephyr Sofa (2013), which has rock formations, have inspiration from nature. As opposed to her aggressive architecture, these are visually lighter and gentle, which embodies her anti-gravity principles. When placed in the spotlight, Orchis will appear lighter than their heavy stereotypes. Mesa shares a sense of floating design with the boat-shaped Broad Museum, and they are anchored to the ground by their internal structures.

Zaha Hadid Design: Untold installation view at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University, 2022. Photo: Eat Pomegranate Photography. Courtesy MSU Broad Art Museum

Hadid’s practice spans different design disciplines in furniture, fashion, home, and architecture, which is incredible. However, fundamentally, these designs articulate Hadid’s understanding of a state of living, as Hadid’s quote on the ground floor’s wall, “Architecture is really about well-being...people want to feel good in a space...it’s about shelter, but it’s also about pleasure.” There is a more visual understanding through the displayed model of the Broad Museum and a series of video interviews with Hadid as well as different image materials. Hadid’s exceptional designs, unconventional viewpoint, and avant-garde attitude propel her to success in a male-dominated industry, breaking through the “limitations of Arab and woman identity” (from an interview with Zaha Hadid by Huma Qureshi in the Guardian). This is a definite lead for all females, specifically for Iranian women who are currently fighting for their rights and future. The Broad Museum has a "leading" meaning for me in the local area. Its transcendence endows the area with another kind of life, cutting through East Lansing’s dreary atmosphere, especially during wintertime. I still remember the sense of shock when I first saw it in 2017, like a fish about to leap tugging at my endless exploration of it. Aiming at its unique imaginative nature, the exhibition has even set up a wall for visitors to answer: “what does the MSU Broad Art Museum look like to you? ”

Under the imaginative veneer, the museum has controversial aspects, such as its disconnection from the neighborhood. It is critical to understand their connections based on their internal logic and abstractions. Craig Kiner and Mónica Ramírez-Montagut talk about, “the facade and shape of the museum are the results of ‘movement lines’ that are generated along Grand River Avenue, as well as those between the town and campus.” One can establish an imaginative sense that the hustle and bustle of the main street on Grand River Avenue and each of our movements converge on these flowing and wrinkled lines of stainless steel. The uniqueness of the building’s exterior defines the unconventional white box form of its interior, which enhances the view while offering more space for different types of artwork.

Zaha Hadid, founder of Zaha Hadid Architects, was awarded the Pritzker Architecture Prize in 2004 and is internationally known for her built, theoretical, and academic work. Each of her projects builds on over thirty years of exploration and research in the interrelated fields of urbanism, architecture, and design.

Born in Baghdad, Iraq, in 1950, Hadid studied mathematics at the American University of Beirut before moving to London in 1972 to attend the Architectural Association (AA) School where she was awarded the Diploma Prize in 1977. Hadid founded Zaha Hadid Architects (ZHA) in 1979 and completed her first building, the Vitra Fire Station, Germany, in 1993. Hadid taught at the AA School until 1987 and held numerous chairs and guest professorships at universities around the world including Columbia, Harvard, Yale, and the University of Applied Arts in Vienna.

Hadid’s outstanding contribution to the architectural profession has been acknowledged by the world’s most respected institutions including the Forbes List of the “World’s Most Powerful Women” and the Japan Art Association presenting her with the “Praemium Imperiale.” In 2010 and 2011, ZHA’s designs were awarded the Stirling Prize, one of architecture’s highest accolades, by the Royal Institute of British Architects. Other awards include UNESCO naming Hadid as an “Artist for Peace,” the Republic of France honoring Hadid with the “Commandeur de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres” and TIME Magazine included her in their list of the “100 Most Influential People in the World.” In 2012, Zaha Hadid was made a Dame Commander of the British Empire by Queen Elizabeth II, and in February 2016, she received the Royal Gold Medal.

Zaha Hadid passed away on March 31, 2016 in Miami, FL.