Some years ago, I got involved in a conversation with another critic that suddenly turned from a modest discourse on contemporary aesthetics to works of art that were “hot” on the market. My colleague’s concerns were specifically related to the work of a conceptually-oriented artist known at the time for his somewhat distant, cynically detached paintings produced by first-rate craftsmen he had hired to work in his studio. The critic exclaimed: “I used to think he was a lesser artist, but now after the events of recent years, I decided he is good.” “Why good?” I retorted in amazement. The critic’s response: “Because he captures the superficial aspect of things in our time!”

Robert C. Morgan works in his studio. Courtesy of Robert C. Morgan

It occurred to me that this was a prescient, yet misleading belief -- that a work of art is good if it appears to reflect or echo the times. Even if the critical context surrounding the work suggests a lesser significance than what is really there, my perspective on the artist’s work to which he referred suggested it was more related to cultural anthropology than to contemporary art. Given the absence of a formidable criterion by which to determine its credibility, I could easily understand how such works might be discussed in terms of the human condition, largely because the research involved in the social sciences is perhaps more neutral, and thus, more symptomatic in recognizing the tenets of a particular culture at a particular moment in the work’s history.

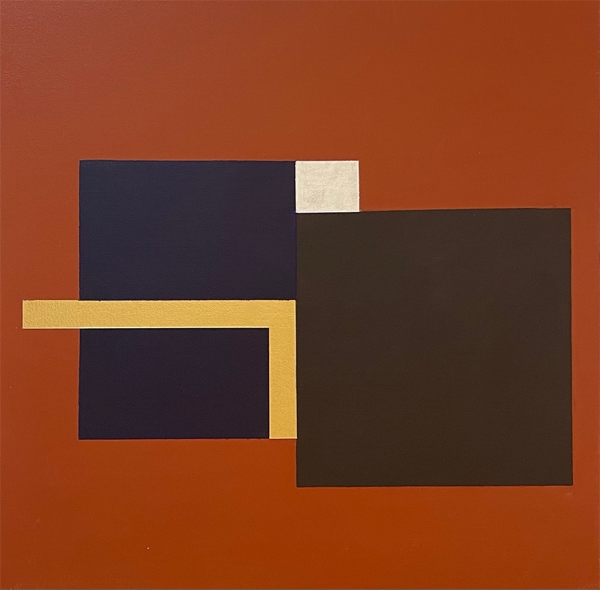

Loggia II, 2019, acrylic, metallic paints on canvas, 56×56cm. Courtesy of Robert C. Morgan

Much of the art being promoted, bartered, and sold on the market today as “contemporary” is, in fact, less about art than about the research that stands behind it. In many cases, this would include the social scientific ordering of objects that are projected within an already given, possibly obsolete, cultural reference. Since the explosive rise of the market in contemporary art over a half-century ago, certain kinds of art have begun to function primarily in terms of their commodity value, in this case, under the rubric of being “conceptual.” These images, objects, and events are fueled through a market-driven domain of stark advertising and promotion. In such an environment, criticism is hardly the issue. It simply doesn’t matter. What matters is how the artist’s work is driven, that is, how it is brought to the attention of the public through promotional techniques, and not whether it carries historical significance. It is mediated rather than understood.

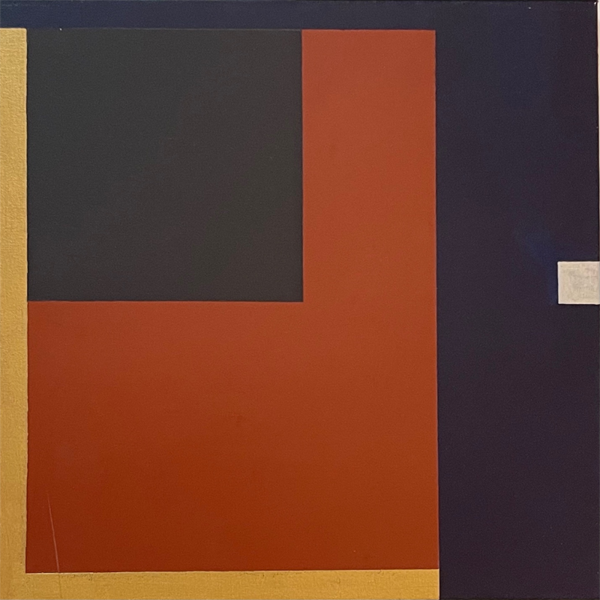

Loggia IV, 2019, acrylic, metallic paints on canvas, 56×56cm. Courtesy of Robert C. Morgan

This is true of much of the work represented in today’s market wherein the work is fundamentally based on trends that manage to escape critical attention often in defense of the galleries and collectors that support them. Parallel to the production of trends in contemporary art, the personal aspect of art has been transformed through the manipulation of detached images in search of commercial appeal. Often these images are relatively mindless, yet capable of accelerating the market into overdrive.

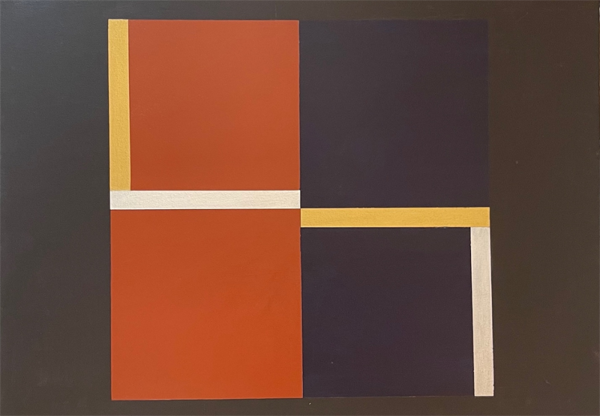

Loggia XIII, 2020, acrylic, metallic paints on canvas, 56×81cm. Courtesy of Robert C. Morgan

Now that the market is in a hiatus (not necessarily a decline), perhaps it is best to reflect on what the market is trying to do next. Is it merely a matter of mirroring what we already know by way of entertainment, fashion, and commercial media? Or will it become more superfluous relative to how we feel living in a world steadily approaching a lust for the artificial? If we choose the latter, art begins to take on a somewhat problematic role, focused on various forms of artifice and socio-psychological obsessions. From a more critical perspective art becomes a mirror of another reality, whereby media on a larger scale inhabits a world devoid of art on a level that proves greater and more efficient than what art can offer us. The seduction of art is finally greater than what it signifies. What does it mean to live in the present – not in the real present, but a copy of the present – a kind of mediated present that is difficult to determine holistically? In the midst of this, how do we rediscover the emotional means whereby we feel the need to return experientially, if not inexorably to art?

Loggia IX, 2019, acrylic, metallic paints on canvas, 56×56cm. Courtesy of Robert C. Morgan

On a critical note, I would like to suggest that there are significant works of art that exist in the studios of artists whose work I have seen directly in various countries throughout the world – artists who are, for whatever reason, disconnected from the existing market, removed from the artificial present. Put another way, they are artists in the real sense, whose work appears significant rather than a symptomatic order of what art is supposed to be at any given time. The artists to which I refer in the real sense are, of course, the exceptions. These are the ones who proceed from a modicum of truth and continue to move in that direction regardless of the social, political, and economic stumbling blocks that are put in their way.

The distortion of this of truth is equal to the desire to meander in a circular orbit, which some artists have done far too often and clearly not to their benefit. It appears that these artists have become symptomatic of their time rather than allowing themselves to become significant. In some cases, they have deliberately removed themselves from the temporal moment in which they live. Their moments of desperation could be read as the point where conformity takes over from where confidence in one’s independence left off.

Cornice 15, 2022, acrylic, metallic paints on canvas, 30×35cm. Courtesy of Robert C. Morgan

This raises another question as to whether what appears symptomatic will inevitably become significant, and vice versa. One might argue that while the conceptualist (mentioned earlier) has more or less retained his symptomatic status throughout his career, his work has yet to appear significant. In the case of another artist, whose early photographs were presumably judged significant quite early on, it appears that in recent years her work has degenerated into a self-endowed quandary of symptomania.

It is curious that the tension between symptomania and significance has not been given more attention in recent decades as made evident in the ongoing conservatism of what we might call the post-Pop phenomenon. Has the informational media that came into aesthetic prominence in the 80s distracted us from seeing the cause-and-effect relationships so evident in the unseen magnitude of the present? There is little doubt that the social theorist Marshall McLuhan was in touch with this line of intrigue nearly two decades earlier; but even so, the comprehension of a division between symptomology and significance was critically weak in coming to terms with analyzing the differences between the two. This weakness was revealed in the dimensions of sublimation that high technology brought to art within the larger scope of pursuing a “global” environment willing to leave culture on the wayside.

Cornice 20, 2022, acrylic, metallic paints on canvas, 30×35cm. Courtesy of Robert C. Morgan

Given the big money interests that support AI (artificial intelligence) as it proceeds to embrace a polymorphic “flow” of hidden information concerning how we think and potentially how we feel, qualitative thinking in relation to art is disappearing into an endless chain of algo-rhythms. These presumably precision tabloids are limited in their stark inability to weigh the importance of qualitative thought. Yet concurrently, without the means of a quantitative measure, algo-rhythms would be unable to function. In other words, the end of critical thought is the price we pay for the sustained use of algo-rhythms, and their futurist applications to art.

Cornice 25, 2022, acrylic, metallic paints on canvas, 30×35cm. Courtesy of Robert C. Morgan

So the question returns to the symptomatic phases of cultural anthropology that have taken over art criticism. Instead of qualitative thinking we are exposed to scholarly research as a means to prove the existence of art, which ultimately cannot be done. To put it simply, art is traditionally less about facts than feelings, the latter of which we cannot define. As the French Symbolist poet Stephane Mallarmé tried to make clear, art cannot be defined, only suggested; and as Duchamp came to reveal in his Ready-mades, they may or may not exist as art. Whether they exist as art or as objects is a matter of choice, even as both cannot exist at the same time. We might say their certainty as art is none other than the exhilaration of their discovery again in the present or, shall we say, at the moment they were seen by an unknown artist, who, at times, made them appear known, possibly significant, or maybe, in some cases, remarkable.

Robert C. Morgan is an international critic, writer, curator, poet, and painter, who lives in New York City. He holds an advanced degree in fine arts (MFA) and a Ph.D. in contemporary art history. He is Professor Emeritus at the Rochester Institute of Technology and Adjunct Professor of Fine Arts at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York. Morgan is the author of Art into Ideas: Essays on Conceptual Art (Cambridge, 1996), The End of the Art World (Allworth Press, 1998), and The Artist and Globalization (Miejska Galeria Sztuki w Lodzi, 2008). In 1999, he received the first Arcale award for International Art Criticism in Salamanca (Spain), and in 2011, was inducted into the European Academy of Sciences and Arts in Salzburg. Dr. Morgan currently writes art criticism for The Brooklyn Rail in New York City. His archive of documents on Conceptual Art is in the Collection of the Hesburgh Libraries at Notre Dame University. Since the 1970s he has maintained his role as an abstract painter whose work was shown in a retrospective exhibition at Proyectos Monclova in Mexico City (2017).