“I have always believed that love is the driving force in one’s life. It is the most powerful, the most wonderful, and the most painful.” As her own life experience has grown, Xing Danwen is sharing her profound insights on sensibility and love.

Sensibility and love are innate topics of human beings, which exists in different relationships, and often vacillate between rationality and sensibility. They do not have specific answers and exact appearances to respond to a wide range of people and matters. Xing Danwen has reflected on these topics and chose to return to the most primitive and natural affection, kinship, in order to trace back, and examine unconditional love, to unveil the complexity of interpersonal and highly emotional relationships. In the two-channel video installation “Thread” (2018), Xing directed a love dilemma. On one side, the mother sits inside the house, sorts out the thread, rolls it into a ball, then knits it into a sweater; on the other a girl unties the sweater’s knot, walks out of the house onto the street. The sweater disintegrates as she runs away. The video, lasting 11 min and 30s, makes no mention of resistance, violence, or bondage. But the metaphorical montage creates a relationship which illustrates the extraordinarily beautiful and painful dichotomy between loving and being loved. Although Xing was not born of the cinematic discipline, her intuition, and experimental approach, deftly blends with her world renowned photographic skill and experience establishing that she not only understands but captures the language of cinema. Through shooting with multiple cameras from different angles, she transformed a simple story into an extraordinary and evocative one. “To turn an ordinary story into a powerful work has always been my pursuit,” she reflected. Xing refers to a movie she admires, “In the Mood for Love” (directed by Wong Kar-wai, 2000), which distills the meaning of the time while establishing a new artistic language. The well-worn story through the use of rich camera language: the other half (the spouses) that never shows up on camera, Su Lizhen and Zhou Muyun passing by each other on the staircase numerous times, and a dimly lit streetlamp in the rain. All of these expressions of camera language symbolically and metaphorically describe the invisible waves and the ups and downs of their liaisons, while also telling the beginning and end of a love story never openly discussed yet desired.

Thread, 2018, two-channel video with Sound, HD, 11’30’’. Courtesy of Xing Danwen Studio

“Whether it is kinship or love, there is a nurturing relationship amongst them, resembling thread and sweater, whereas some sweaters eventually are woven into emotional cages that give rise to power struggles. Loving and being loved are manifested by motivation and effect, but things frequently go against the grain, result in confrontation.” Following her exposition, it seems as though Xing acts out the love and being loved: the lover initiates the act of loving, which is equal to those in power; the beloved is the receiving end, proving the validity of love. When the latter fails to experience the sensation of being loved, a love tragedy ensues. Subsequently a battle wages and the beloved initiates a rebellion against the power (of the lover) and acts escaping to freedom. We naturally form affectionate bonds, yet only some collisions, generate different fluctuating feedback, either positive or negative, causing the formation of a chasm. “When we act on our desire to love others, sometimes they do not feel being loved but instead feel emotional entitlement being imposed and violence being inflicted. This is blind love, which is based on one’s own perspective and completely ignores the fact that people have ‘individuality. So often you hear what I say, but do not truly understand what I am saying. It will be hard to iron out interpersonal conflicts if we are unable to recognize this constant occurrence,” Xing expressed. There is a brief passage that provides a similar explanation: the table and the chair were built on opposite sides of a wall, looking toward the unbridgeable gap. She was desperately shouting and waving, but he could not hear or see anything. As a result, one goes to ponder what is the motivation and role of language in existence. They seem to see the meaning of words, but they are unable to hear the voice of their heart. In the unknowingness, they are concealed. As in the case of the pair of the mother and daughter caught in the “sweater dilemma,” who are drowned in the tangled threads and struggled in a way silently. The girl untied the sweater knot, ostensibly to escape, but it is also a remedy for the broken kinship. Xing believes that “the reality of love and hate in affections is a soap opera that is hard to bypass and never to grip.”

Thread, 2018, still images. Courtesy of Xing Danwen Studio

Elena Ferrante's novel “Troubling Love” also features a mother and daughter, telling the story of the daughter Delia's complex feelings for her mother Amalia while insinuating the living conditions of Italian women at the time. The daughter in the film adaptation of this novel ends up wearing her mother's suit and replacing the novel’s “Amalia existed, I am Amalia” monologue with one in which she allows people on the train to call her “Amalia.” This suggested, in a nutshell, that Delia has reconciled with her mother and has grown into an independent and mature woman. The journalist named Annamaria Guadagni wrote Ferrante a letter in which she asked, “the mother-daughter relationship is feminine in its subtlety. To have her own identity, the daughter must go through a difficult struggle, namely, breaking away from her mother and becoming herself. The novel starts with two women who appear to blend into one by the end. So, does the daughter ultimately lose or find herself in this way?” Ferrante modified this question and then responded to it by declaring that becoming one with one’s own mother does not imply losing oneself and one’s identity as a woman. So, does the image on the left “Thread,” in which the daughter accepts her mother’s hug, represent reconciliation? Or does the image on the right, in which she breaks free of her sweater and crosses the gap of reality to gain understanding and become herself? Similarly, Xing Danwen did not respond directly to my question but instead expressed that one’s motive of kindness will resolve the contradiction and transcend the emotional conflict. As for the end, it can only be understood but not be explained in words.

Thread, 2018, two-channel video with Sound, HD, 11’30’’. Courtesy of Xing Danwen Studio

A film director from New York who had watched “Thread” commented that this work seems to discuss two separate stories, but the end forms a cycle. It, therefore, actually contains two beginning and two ends. Following this context, I would like to interpret the girl’s final running behavior as a kind of “runaway.” This is because her actions remind me of the middle-aged Chinese woman who was reported by the media using the hashtag “runaway.” She escaped her family relationship by taking a solo drive to live her own life. Xing Danwen admits to running away many times in her life, but she prefers to describe this experience as “uprisings.” There is no doubt that one can merely “rise up” in the face of trouble and pain.

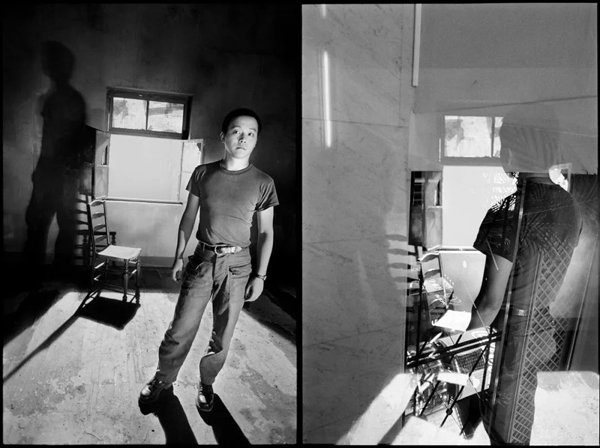

Xing Danwen in her New York apartment in 1999. Courtesy of Xing Danwen Studio

Xing absolutely has an unruly side since childhood although she was born in a good family of intellectuals, grew up as a good kid, with excellent grades in school. It was not until she was in high school that she began her first " rebellion " - against her parents' suggestion to study painting instead of back taker the entrance exams for Tsinghua and Peking University. With her talent, she stood out among over 6,000 applicants and was one of the 30 freshmen admitted to the High School of Fine Art affiliated with Xi’an Academy of Fine Arts. Later, owing to her outstanding academic performance, she was directly recommended for admission to the Xi'an Academy of Fine Arts in the first place. She, however, declined this honor and went to Beijing to take part in the college entrance exam for art. The result was that she was eventually dropped out of school and set as a negative example by the school because she was reported by the other candidate’s parents with the name of violating the policy (she could not take the recommendation for admission as her safety school). This was undoubtedly a dramatic setback for her as a teenager, but thanks to her determination and efforts, she was admitted to the China Central Academy of Fine Arts (today's Department of Experimental Art). Upon her admission in 1988, followed by the historical events of 1989, her parents persuaded her back Xi’an where she insisted on staying at school until the situation calmed down. She explained, “I thought it was the right time to go so I headed alone with a camera and a map to the Taklamakan Desert, which is Sanmao’s “the Sahara Desert” in my mind [1]. Although the journey was potentially unsafe, fortunately, nothing serious happened, and I returned with a dozen rolls of photos I had taken.”

Xing Danwen in the lab of SVA School of Visual Arts in New York in 1999. Courtesy of Xing Danwen Studio

A Personal Diary – Dou Wei, 1995, Beijing, Courtesy of Xing Danwen Studio

This was a meaningful and affirming “uprising,” which was her first foray into the distance, and more importantly, was the beginning of perceiving the world with a camera and defining her perspective. Since then, photography has been her main creative medium. With deep interest and passion, she has stepped into this artistic field that was almost empty at the time to explore the limits and contemporaneity of photography. Early on, her lens was always focused on her own time, life, and friends, such as the 1990s representative work “A Personal Diary,” a documentary image of the generation of pioneers born in the 1950s and 1960, and “I Am a Woman,” which concerned about female identity issues. Up until 1998, she received two scholarships (ACC Grant “Asia Cultural Council in New York” and the SVA President's Scholarship) to study in New York, which offered her an “uprising” opportunity, or literally a “challenge” she had always desired. Studying in this international contemporary art capital not only broadened her horizons and improved her knowledge of contemporary art but also enabled her to achieve a huge leap in her creative skills—from traditional mediums to digital, from still photography to moving images and multimedia installations. Simultaneously, she abandoned her previous photographic approach and instead adopted creative methods such as “hidden” or “self-acting” to demonstrate the visual image of “human” and the theme of “human predicament.” She went to New York in 1998 and returned to China in 2002, during which her art had also undergone a coincidental “cross-century” transformation. “Before 1989, I grasped the camera like to take a machine gun, facing the ‘forbidden’, aiming at the crowd, and rushing towards the ‘happening’. Although my documentary shooting yielded many excellent and historically valuable images, it also made me tired of ‘people’ and ‘man-made’ pressures,” Xing told me. “I left Beijing because I desired to make a change. During my time in New York, I learned new techniques and ideas. In a more challenging environment, I wanted to re-examine myself, consider my future creative direction, and to adjust my own creation as well as my mind and body.” After getting back to Beijing in 2002, Xing Danwen immediately became concerned with China's rapid development. Her works are set against the backdrop of the times, responding genuinely to urban development, the state of being of urbanites, and the relationship between private space, public space, and subject space.

Prescription for Life, 2019, 12’30’’. Courtesy of Xing Danwen Studio

In “Prescription for Life” (2019), “A Home of One’s Own” (2019), and “Wall House” (2007), she focuses on people’s inner minds. “Prescription for Life”, a performance and video work related to the piece “I Can't Feel What I Feel”, originated from her experience of seeing doctors for years and taking medication. This video depicts the whole process of her swallowing medication, with colorful pills and capsules of various sizes placed on the table. She gradually agitated from the initial calm pill-taking into a frenzied state of devouring. This transition is analogous to the parent who swallowed foods in the animated film “Spirited Away”, evolving from a civilized posture to a primitive one also. Aside from the main character, the drug, which is portrayed as a live trap, is the most prominent symbol in this work, symbolizing the endless desires of contemporaries and an “excessive positivity”, or in other words, an extreme and excessive certainty. Man's capacity for self-rejection is then deprived, and they are eventually driven to burnout and destruction in the frenzy of self-competition and overwork, like “a humanity waging war on itself” (from “Burnout Society”). Xing’s artistic prescription that people should avoid being imbalanced in the “life is endless, desire more than” appears to be cautious. Furthermore, owing to the special effects, the “person” (self-acting) has been flattened and symbolized, and the colorful nature of those drugs has also been highlighted. In my humble opinion, this endows drugs with another layer of “functional symbolism”, implying that it is the embodiment of individual vitality, existence, and consciousness. In the movie “The Father” (directed by Florian Zeller, 2020), the “watch” is an essential object for the sick father to perceive his existence and consciousness during the chaotic structure of time. He says at the end, “I have nowhere to put my head down anymore. But I know my watch is on my wrist, that I do know.” In "Prescription for Life" and “Thread”, the connection between medium and themes, and their mutual expressiveness, established by Xing, are a pun and a highlight of artistic wisdom.

Prescription for Life, 2019, still images. Courtesy of Xing Danwen Studio

If “Prescription for Life” embodies a door that is deep within her heart, then outside the door, she has crossed several thresholds of external observation and survey. Xing came to Beijing in the late 1980s, went through several relocations, and witnessed the transformation and changes of the city. She gradually moved away from the city, from the center of old Beijing to the suburbs, from within 2nd Ring Road to outside the 6th Ring Road. As she said, “I am a typical ‘individual’ in the urbanization process.” The city’s swiftly bristling skyscrapers constitute a scene from afar: a small and dense window with different individuals living in it, exposing their lonely situation who are separated by a wall. The prosperity of the external world and the loneliness of people’s inner souls created a contrasting scene, which is deeply rooted in her heart. Subsequently, she was invited to the artist residency program of Wall House Foundation, after her piece “Urban Fiction” was favored by the curator. When confronted with John Hejduk's famous building, she decided to implant “loneliness” into this creative theme. Meanwhile, she combined the seemingly irrational physical architecture of Wall House—a large wall in the middle of a small house—to adumbrate human psychological dilemma. The final installation works featured four window-like images, each with a “person” sitting alone in the room, and each window view was printed as a skyscraper and street scene of a bustling city. The relationship between “one person” and “one city” is reinforced. This work’s animation video also embodied the individual’s solitary as well. She walks quietly through the bedroom and the door is closed heavily, breaking the still atmosphere between quietude and motion, and the audience is brought into the helpless reality: one’s home, one’s own life, and one’s own companion (from the statement of “Wall House”). This is akin to the table lamp shrouded in dim light, a chair, and the person’s silhouette sewn on the wool carpet, exuding the same sense of solitude within easy reach yet far from each other, where one is the shadow of oneself (“A Home of One’s Own”).

Wall House, 2017, multimedia installation (photography and video). Courtesy of Xing Danwen Studio

Wall House, 2017, multimedia installation (photography and video). Courtesy of Xing Danwen Studio

Installation view of Wall House, Red Brick Art Museum, 2017. Courtesy of Xing Danwen Studio

Installation view of A Home of One’s Own, SPURS Gallery, 2019. Courtesy of Xing Danwen Studio

As the “urban two-part series,” both pieces rhyme in a conflicting and harmonious manner in the intersection of fake (scenery) and real (person) / real (objects) and imagery (shadows). The third part, “Urban Fiction” (2004-2020), also intertwines the real with fake and real with the imaginary. Xing photographed the fake property models that illustrate our real-living scenarios first, and then digitally grafted various imaginary characters that she played, such as shopaholics, perpetrators, and love killers, onto the photographs. As roles change, so do the viewers, who have transformed into a watcher with no recklessness, a voyeur with sinister intentions, and a supervisor with digital control. Xing, in the way of playing by “self”, acts out diverse urbanities that made up the city’s phenomena as well as their lonely and anxious side. Be it in her previous back or silhouette, or in various roles, she explores the truth of how one can reconcile oneself with life. She does not palpably negativize this human attribute, yet visually interprets loneliness as a norm in the modern city and a garden for people to befriend themselves. This is in line with the woman in “Wall House” who looks into the mirror but sees another woman’s face reflected in it.

Wall House, 2017, multimedia installation (photography and video). Courtesy of Xing Danwen Studio

Urban Fiction, 2004 – 2020, photography with digital manipulation. Courtesy of Xing Danwen Studio

Xing is also aware that on the other side of urbanization, there exists the impact of rapid economic development of cities on people and the environment. In 2002, she took several field trips to the Pearl River Delta region of Guangdong, where she witnessed the polluted landscape created by western electronic waste, which is still disposed of by primitive methods such as demolition and burning in local towns. The “guardians” were wage earners from different parts of the country, who were “disconnected (isolated)” from the outside world by living in radioactive garbage, breathing in burned rubber and plastic, and drinking contaminated water. Hence, they are also removed from the final image (previously mentioned as the way of “hiding”), which consists solely of some physical materials taken by the method of microscopic photography, such as computer parts, chips, and cables. Wherein some of the details, like the traces of human use, component trademarks, and handwritten notes, are clearly visible. This conceptual approach highlights the paradox of workers’ existence, that is, who have contributed to the city but have been neglected in the e-waste, as well as the environmental cost of e-waste. The work's overall composition is an overhead geometric abstraction, resembling the city's structure in Google Maps. Xing gave up her previous record and documentary form of photography, intersecting in microscopic and distant views. The “disCONNEXION” thus embodies the visual temperature of Western abstract expressionism, allowing the discarded object to undergo an aesthetic metamorphosis. Darlene Lee “analyzed that ‘...hard images’ have been turned into ‘something beautiful, abstract and powerful’”; and Felicia Pfister uses “the term ‘strange beauty’ to conclude ‘the grey tones of the ugliest materials’”. When it was first exhibited at The American Effects (Whitney Museum of Art, New York), curator Lawrence Lind chose it for the exhibition invitation and catalog’s cover, and said, “The visual abstract beauty of this work and the nightmarish message behind it create a solitary contrast that makes the work distinctive and thought-provoking.”

disCONNEXION, 2002-2003, photography. Courtesy of Xing Danwen Studio

Image 1: Installation view of On Reason & Emotion, 14th Biennale of Sydney 2004, Museum of Contemporary Art; Image 2: Installation view of The American Effects, Whitney Museum of Art, New York, 2003. Courtesy of Xing Danwen Studio

“Because I am in the Mountain,” Xing’s other installation work, also contains this contrasting technique in a medium contrasting manner to reflect the aesthetic strategy—the poetic beauty of the natural landscape opposes and parallels the environmentally polluted coal cinder—outlining a landscape of mountain and river as if throughout the lands. Xing created this installation using props and models while inspired by the coal cinder’s characteristics. On one side, there is a pristine mountain and flowing water, sporadically dotted with trees and grass houses, like a classic Chinese poetic ink painting; on the other, there is a suburban town, villas, highway, and gas station configuration, and even a real estate. The whole scene is unoccupied, but human traces and human behavior in nature are ubiquitous. “This work stemmed from the experience of my studio being forced to move to the outskirts of Beijing and depending on coal to heat the house during the winter. I recalled the air pollution in Beijing was also more severe. When I was digging out the coal, I noticed some of them that could not be burned away by the fire and were twisted together with a beautiful metallic texture, which reminds me of a thousand strange miniature scholar’s rocks [2]. I started to collect coal cinders and conceptualize how I can use them to express my concerns about the environment and the destruction caused by urbanization. Eventually, I came up with the concept of reverse representation, namely shaping beautiful scenery with coal cinder. ‘Because I am in the Mountain’ is the famous poem by Su Dongpo [3] which originally describes people’s inability to see the gorgeous mountains due to limiting themselves in peaks, is paraphrased in my work as the phenomenon that mankind’s shortsighted in urban development has led to environmental damage. Simply by being in the midst of it and ignoring all environmental problems.”

Because I am in the Mountain, 2017, installation with coal coke and mixed materials. Courtesy of Xing Danwen Studio

Xing’s art emanates her social conception everywhere, which, overall, are two complements of each other, and thus, her works possess a grand narrative and humanistic concern. This may pertain to the experience that she was a freelance and professional photographer for six or seven years after graduating from the Central Academy of Fine Arts in 1992. She has shot many features on humanistic and social topics for Time, The New York Times, South China Morning Post and Libération, etc., and her work has been appraised by many editors-in-chief having Magnum’s linguistic depth. “This experience has brought me more consciousness on social issues and arts and cultural situations, from multiple standpoints, as well as to skillfully survive and work in the context of conflicts and taboos. All of these have enabled me to be more critical. My class teacher at the Academy of Fine Arts met me thirty years later and lamented the fact that I was the only one of his students who did not follow the path and China’s system but succeeded anyway. Indeed, I have always been a rebel, refusing to live by the book, undergoing numerous rough times as well as encountering many surprises and miracles. So, until today, looking back, I see a clear trajectory.” Xing is an observer and activist running through the social jungle, which is how I would describe her practice. In a grand narrative viewpoint, she is concerned about the specific human; in rich and complex humanity, she throws a warning stone. “I enjoy observing and analyzing the people and events of daily life,” she states. “And probably they will be turned into my artworks one day.”

Because I am in the Mountain, 2017, installation with coal coke and mixed materials. Courtesy of Xing Danwen Studio

Beyond being an artist, Xing is a naturally observant woman with a sharp perspective. Being an artist and a woman are equally essential identities and roles for her, but each comes with a set of predicaments. A male German artist once told her, in a complimenting tone, that, female artists can rely on their gender charisma to gain more opportunities to thrive in a male-dominated society. “That’s definitely the worst of it,” she immediately retorted. On another occasion, when she attended the opening reception of her exhibition in elaborate attire, the person sitting next to her at the dinner asked her what she did for a living. She was stunned and concurrently realized that the juxtaposition of a female artist and dressing pretty had only resulted in misunderstandings. Even her art has also gone through a long period of being underestimated. Yu-Chieh Li in the introduction of her essay “Gender and Performativity in Xing Danwen’s East Village” [4] mentions, “The second issue that Wu Hung chose not to mention is why Xing’s role in creating the East Village canon is omitted entirely from many major publications on performance art in China.” One possible explanation for this proposed by the author is the prevalence of phallogocentrism in the Chinese art world (but this is not the focus of the full discussion). Xing was surprised as well when she first read this point, “as if she was overturning this for me (laughs), I hadn’t thought about it myself, nor had I read Wu Hung’s books carefully. I didn’t have preconceived female perspectives while creating since I obsess over the ideas of the ‘human being’ itself. Many people who saw my works were unaware of the artist being a woman in the early years. After the show at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 2003, I remembered that the New York Times even ran a page to correct the gender error. Certainly, different emotional characteristics and perspectives involve female precognition. That is sure and natural.”

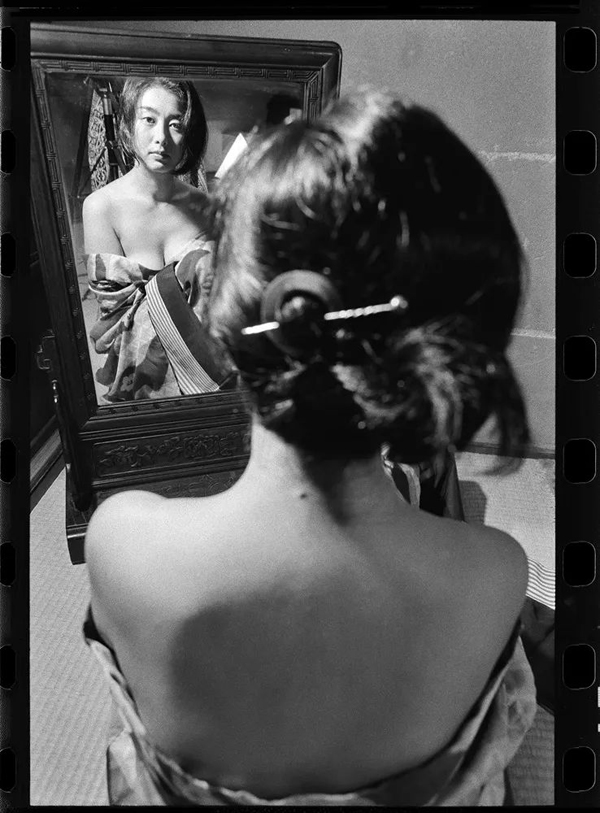

I Am A Woman, 1994-1996, black and white photography. Courtesy of Xing Danwen Studio

In this way, the black and white photograph “I Am a Woman” is unquestionably the work most related to her female identity. Xing considered this set of works, centered on her female friends, as “self-portraits”, since they not only dissolve the male gaze, but also interrogate the issue of “women” as a woman, from female gender and female identity to various roles such as natural gender roles, male imposed roles, traditional family roles, social roles, and more. As noted by Silvia Fok (Fok, 2014, 262), critic Gu Zheng has commented this piece is the first-ever photograph of female nudity shot by a Chinese woman, as they had belonged to the subject of male artists in the past (Gu, 2006, 91-6). Doubtlessly Xing is audacious and avant-garde, revealing the enormous perplexities faced by a large group, and these perplexities indicate that they have yet to reach the most fundamental point in gender rights. They remain in a situation that requires them to examine themselves, fight for themselves, and overcome the problems that history has leftover for them—just as abruptly turning over the soil and revealing a swarm of fleas trying to hide beneath. And their enriching spiritual values are still treated as by-products or appendants to be discarded by others who try to retain a sense of superiority.

Installation view of I Am A Woman at UCCA Center for Contemporary Art, 2019. Courtesy of Xing Danwen Studio

A female artist thus faces a threshold that must be overcome in order to keep effectively in a male-dominated art world. Like the previous “revolution (uprising),” Xing has done it on her own, and once again has gained equality and a position by relying on her own efforts. Perhaps this striving is the fulfillment of the most precious part—the equality of human beings. And yet, how is this not the circumstance to preserve the result that is vulnerable to losing? (Elena Ferrante stated in the book of Frantumaglia: A Writer's Journey (2016) that “the freedom that women have inherited is not part of the natural state of affairs but the temporary outcome of a long battle that is still being waged, and in which everything could suddenly be lost.”) Xing has a strategic, rather than radical act, and believes that “people differ only in intelligence and stupidity, not in gender. So, people should not be treated as subhuman and denied the right to achieve self-actualization because of their gender.” This is inextricably linked to her upbringing in a family where her parents advocate for women’s independence and autonomy, as well as her growing up during Mao’s era when the slogan—women can hold up half of the sky—was widely used. She has both internal and external conditions and at the same time insisted on being herself. When women are objectified, as a result, she does not retreat from being defined by men; even when relegated to “woman,” she retains faith in the dignity and image of being a human being, because “before being a woman, I am first and foremost a human being, a person who is equal to all people.” Xing, who was born in 1967, is more than twenty years apart from me. Our society is developing, and we are all contributing to its course in our own way. Dawn, I believe, is coming ahead of us, so we as women must not give up ourselves.

From inside the lens to outside the camera, Xing has never relinquished her ongoing passionate love affair with photography, nor has she forgotten her conviction to carry on with her art to the end. “I hope to be healthy and energetic and keep the creative spirit until the end of my life, like the great artists, Louise Bourgeois and Frida Kahlo.”

Xing Danwen at the show “Prescription for Life”. Courtesy of Xing Danwen Studio.

What about the present? “Keep working, remain calm and resilient, and have a clear vision.”

[1] Sanmao was the pen name of Echo Chen Ping, a Chinese writer who wrote the book of Stories of the Sahara.

[2] Scholar’s rocks, which is the English term for Gongshi, are naturally occurring decorative stones which are traditionally appreciated by Chinese scholars.

[3] Su Dongpo, also known as Su Shi, is a Chinese scholar-official of the Song dynasty.

Because I myself am in the mountain by Su Shi

From the side, a whole range; from the end, a single peak:

Far, near, high, low, no two parts alike.

Why can’t I tell the true shape of Lushan?

Because I myself am in the mountain.

Translated by Burton Weston

[4] Yu-Chieh Li (2021) Gender and Performativity in Xing Danwen’s East Village, Third Text, 35:3, 389-410, DOI: 10.1080/09528822.2021.1915630.

Xing Danwen was born in Xi'an and currently lives and works in Beijing.

Being part of the 90s Chinese Avant-garde art, Xing was one of a few artists in the late 80s and 90s in China who was exploring the boundaries of photography and using photography as an art form. She observes and challenges China's social issues, humanity, female identity, and the generation born in the 60s through the camera.

She works constantly with photography, video, mixed media and installations to discuss subjects including cultural dislocation, conflicts between globalization and traditions, environmental issues caused by the development, and the urban drama between desire and reality.

As a woman and artist, Xing has actively exhibited in numerous museums and biennials/triennials, such as the Sydney Biennale, Yokohama Triennale, The Whitney Museum of Art in New York, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the International Center of Photography in New York, the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, the Pompidou Museum of Modern Art in France, the Victoria Museum in London and the Ullens and Red Brick Art Museums in China, etc. Her works are also widely collected by the aforementioned institutions, and many notable private collections such as Sigg Collections, Swiss Bank, French National Art Fund, etc.

With her artistic achievement, Xing's work has been widely published in many important volumes as part of the academic discourse in the international art world, including the latest masterpiece “Great Women Artists” by Phaidon UK. She has also received numerous awards, including the 2003 Arles International Art Festival for the Best Publishing Project; the 2008 Netherlands ING Photography Award for the finalists. AAC awarded her the Silver trophy for Best Artist of the Year in 2018. In addition, she was named the 10th “25 Asian Art Female Power” by Art Bazaar magazine Japan in 2019.