Yan Li, a core member of Jintian (Today) and the Stars Art Group (xing xing), has been involved in both poetry and painting since the 1970s, producing a plethora of high-quality “philosophical products.” His method of seeking human civilization, freedom, and truth is to name a poem after a painting or to recite a painting after a poem. With the “anti-distortion” attitude, wonderful and imaginative sense of images, and intellectual writing style, he digested the wounds of the era and all human nature. We can still find his perseverance and faith in civilization if getting down to his works. Yan Li travels abroad with his mother tongue and returns to his homeland within the mother tongue, giving the impression that he is a rebel, but he is actually suffused with passion and responsibility for his homeland. On numerous occasions, he has stated that “writing poetry helps one build a civilization within oneself.” Based on the present, let us keep the civilization’s memory alive through his poems and paintings.

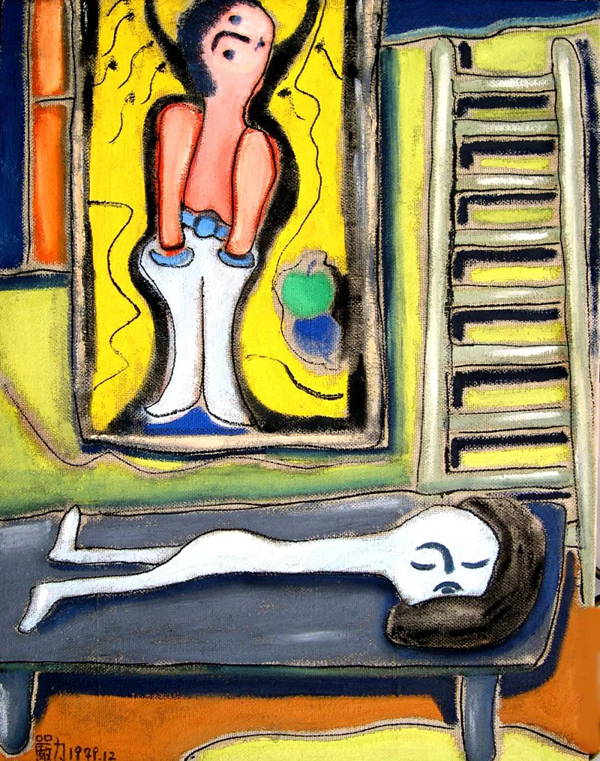

“Things on Earth ......” 1994, Yan Li

Things on Earth are not even discussed with Earth

Hu Lingyuan: Tell us about your recent creations, do they respond to the current situation?

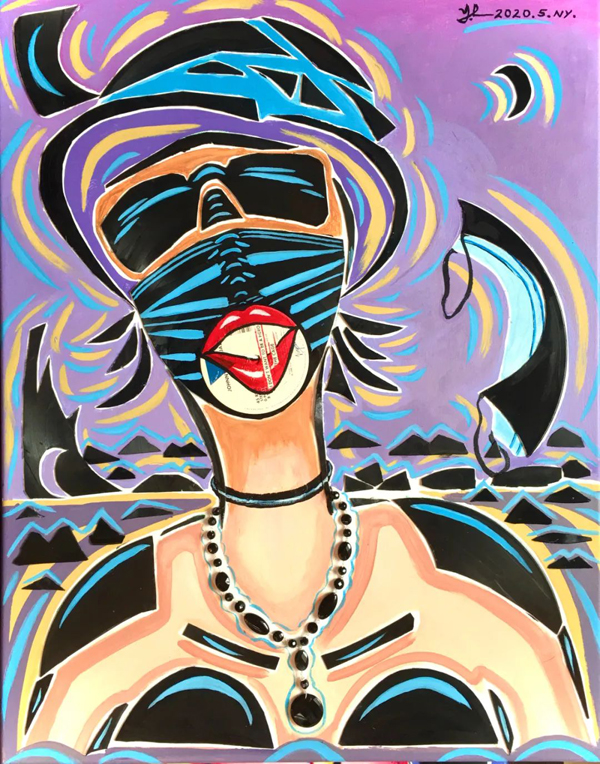

Yan Li: Some of my works are about my feelings and views on life, while others are re-expressions of eternal themes, such as war and love. When I encounter social events that can be easily re-expressed or transformed into a sense of image, I will create them. During the pandemic, for instance, I painted a classical sculpture with a mask in my hand.

Yan Li: I also composed some poems. However, poetry is powerless in the face of different sudden and violent social events because it can only be used to appeal or express anger. Legal intervention and truthful media reports are the most effective methods, as seen in the recent Russia-Ukraine war, where truthful information is extremely important. There is too much false information that confuses the public owing to the advanced network. At this point, the media is a double-edged sword, and it is particularly challenging to weigh its benefits and drawbacks and identify the truth. I am certainly reacting to recent events, but as a poet, I am also aware that the effect of a poem takes time to settle down.

Multiple Memories at Home During the Pandemic (1), 2020, acrylic on canvas, 76×61cm. Courtesy of Yan Li

Hu Lingyuan: You wrote a poem about the Iraq war called “Autumn 2003.” What are your thoughts and appeals to the distant war and the suffering around you?

Yan Li: Natural and man-made disasters continue to strike the earth. Natural disasters demonstrate that our understanding of nature is still superficial, and whiles some natural disasters have been overcome, they are far from sufficient. The pandemic is caused by a virus, but has human behavior played a role in its occurrence? It is also something that should be reflected on and researched. Speaking of man-made disasters, I think we, as part of society, should do our part. Poets and painters can write poems and paintings to appeal; journalists must report the truth; workers and employees should work hard. Everyone should play their own area of expertise, then do their own job and serve others. If everyone does their part, a relatively harmonious society will emerge. Of course, our society must also build and maintain an environment in which people compare goodwill rather than evil with one another. In this way, civilization will have a solid foundation from which to grow. In addition, civilization is not about obeying the law out of fear of punishment; rather, under the premise of compliance, one must continue to cultivate one’s own cultivation and aesthetics, which is something that everyone must implement on his or her own, instead of relying on the state and nation, religion, and others to do it for oneself.

Swan in the Lake of Records, 2021, acrylic, and vinyl on canvas, 108×104cm. Courtesy of Yan Li

Hu Lingyuan: I recall you also stating that writing poetry helps one build a civilization within oneself.

Yan Li: Yes, writing poetry is the process of thinking because it’s not only about how to phrase sentences but also about how to reflect on your own values and how to let others understand your point of view and the “philosophical products” you desire to deliver through poetry. The spirit of human poetry is a critique of society’s dregs and a questioning of human essence, as well as the pursuit of ideal and perfection. Therefore, I think that people who write poetry and writing have a better chance of developing civilization in their bodies. However, this does not imply that people who do not write poetry or writing do not think; they do; they simply do not extend the products of poetry, fiction, and painting. People in different professions, on the other hand, can manifest themselves in various ways, such as a gourmet making a delicious dish to serve others, which is also part of building a civilized life, and every part of it is vital.

Love Can't Be Bought with Money, 2021, acrylic, and vinyl on canvas, 100x76 cm. Courtesy of Yan Li

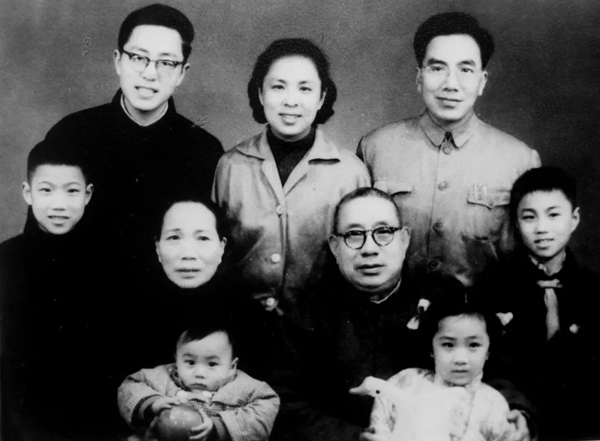

Hu Lingyuan: The death of your grandfather must have hit you hard during that special time. This kind of instantaneous growth makes you realize that your childhood is far away from you. How did you pass through it? (Yan Cangshan, the founder of the Chinese National Medical Center, was the director of the Shanghai Ren Ji Shan Tang during the war against Japan and was in charge of medical treatment in the refugee shelters; he was also invited to treat Lu Xun by the left-wing writer Ruo Shi; he elected as a member of the 5th Shanghai CPPCC.)

Yan Li: People have a strong will to live, which makes them keep tough to get through those difficult times. But for people with relatively weak tolerance and a straightforward personality, that is hit a rock with an egg, leading to destruction. My grandfather, who had practiced medicine in Shanghai his entire life and was highly respected, had a great influence on me and then passed away during that time. After that, those collections of Pan Tianshou, Zheng Banqiao, Tang Bohu, and other valuable ancient paintings and calligraphy were then burned. Later, due to illness, my father also passed away. These sad memories accompanied my mental development during my youth, which enabled me to restrain my normal desires a little more. Surely, the material conditions and circumstances at that time were also limited.

Family Portrait of Yan Li, 1964, Shanghai. Yan Cansan (the second row, 2nd from right), Yan Li in the third grade (the second row, 1st from right). Courtesy of Yan Li

Hu Lingyuan: What state were you in when you wrote, “Give It Back to Me” (1986)?

Yan Li: I wrote it in 1986 after arriving in New York at the age of 31 in 1985, after the reform and opening, because I had lived in different countries and found that all human beings have the same aspirations for a better life. It is just that humanity must be open to the ultimate issue of how to collaborate for common interests and build a better life on earth. This poem is intended to be an appeal.

“This Pair of Eyes” 2018, Yan Li

I am fascinated by a verb that can link tearful shimmers

Capable of representing whole lakes and oceans

I am fascinated by their vision, which hangs up scenery anywhere

Hu Lingyuan: Chinese literati frequently claim that poetry and painting emerge from the same origin, but there is an opinion of the Limits of Painting and Poetry in the West. How do you express their relationship in your creation based on your personal experience?

Yan Li: The goal of literature and art is, to begin with, aesthetics, to eliminate the need for merely animal organs, and to gradually accumulate and lay the groundwork for a more solid human civilization. As a result, poetry, calligraphy, painting, and music are actually complementary and mutually compatible. With this concept of mutually compatible, my creation will gain more insights. I believe there is no contradiction between the senses of picture and musicality in poetry; the poetic and musical sense in painting; the poetic feeling in music; only a more fluent and complete aesthetic.

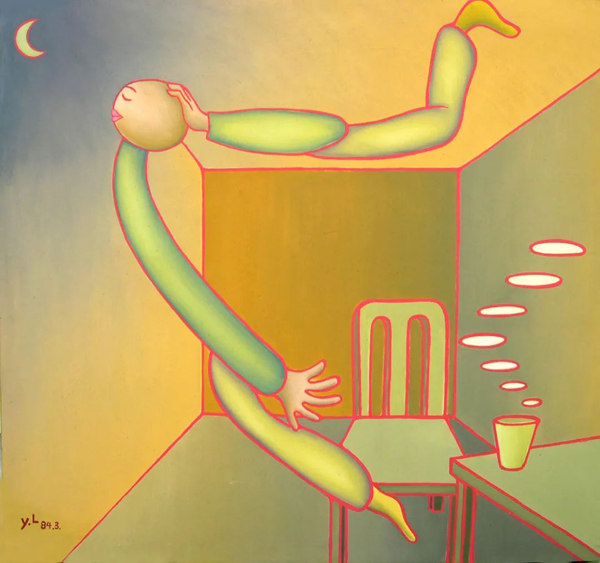

Drinking Music, 1984, oil on canvas, Beijing. Courtesy of Yan Li

Hu Lingyuan: Your grandfather collected many ancient paintings and calligraphy, which was a big inspiration for your art. Why did you start painting until adulthood? Is your group of works on paper in the form of inscriptions related to your grandfather’s collections?

Yan Li: It was a combination of my grandfather’s ancient painting and calligraphy, such as the works of Pan Tianshou, Zheng Banqiao, and Tang Bohu, and of the museums, art galleries, and the event I saw in society. Childhood is the age of absorbing knowledge and accumulating insight, and merely when the body develops into youth, we have the physical strength and energy to do things. It is then that what was previously absorbed manifests itself. Was I born with a talent for literature and art, or did I grow up seeing too many collections of paintings and calligraphy, which influenced me to pursue a career in literary and artistic creation? It is hard to say, but the reason I use words to convey my heart is that I have too many emotions inside that need to be expressed. I became addicted to writing and addicted to painting because I have a lot of concerns about society. And poetry and painting are the best way that enables me to transform them into artworks under the right conditions.

Pleasantly Sleepwalking, 1984, oil on canvas. Courtesy of Yan Li

Hu Lingyuan: How do your parents feel about your involvement in these poetic and artistic activities?

Yan Li: They were relieved and reassured that I was not just doing nothing to get by. They said it's not a bad idea for you to work as a factory worker after being out of school for more than ten years. Later, they were happy to see that I was writing and painting in addition to working. My mother graduated from the chemistry department of the Sino-French University in Beijing, and my father graduated from the chemistry department of the University of Shanghai. Both work in the State Scientific and Technological Commission of The People's Republic of China, which was later combined with the Chinese Academy of Sciences. So, my parents were considered senior intellectuals. My interest in art was more related to my grandfather, and my grandfather's grandfather was a painter who lived in seclusion in the mountains during the late Qing Dynasty. Pan Tianshou, a friend of my grandfather from the same village, even came to see my senior grandfather's paintings. My grandfather's calligraphy was very excellent, and he enjoyed collecting ancient paintings and calligraphy, so I think there is some relationship with his artistic sensibility.

Sketch, 1979, oil on canvas, Yan Li's dormitory at the Beijing No.2 Machine Tool Factory. Courtesy of Yan Li

Lingyuan Hu: Did you consider attending a professional art school?

Ying Li: Professional colleges and universities provide educational opportunities, but professional training may not be the only way for a poet or painter to become a good poet or painter. I believe that concept and practice are more important than talent and diligence, and I work very hard in my creative work. I paint, write poems and novels, and run a magazine, so, to paraphrase a popular saying, I am fired up! I enjoy the process of creation, and in order to keep enjoying it, I must keep creating. I began painting not to sell or support myself as a professional, but to express myself freely. Many artists' works are now programmed to work with galleries and curators to be marketed.

The stars say: please accept my thanks in the sky – Yan Li

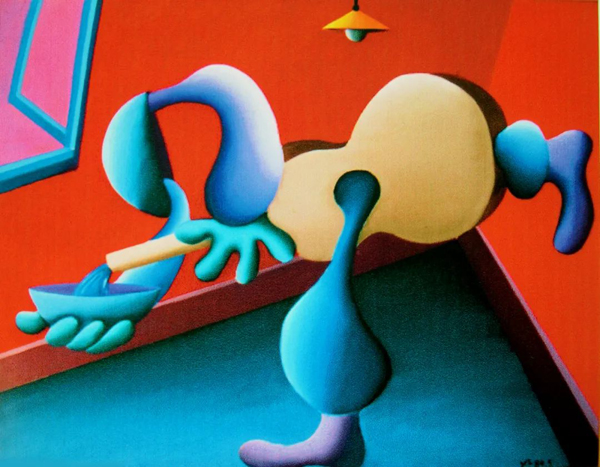

Hu Lingyuan: Your early works reveal modernity, such as “Even the Chairs Want to Leave Home” and “Combing Music.” What inspired your stylistic expression in these early works?

Yan Li: That is the concept I mentioned earlier; skill is for ideas and concepts, and skill can be acquired in two ways: school and practice. However, because of objective factors, I was not able to go to school, so my survival skills have been accumulated through years of practice, and the survival skills also include the creation approach of literature and art. As for my painting style, it is to make each painting interesting; they should be the product of thinking and aesthetics, not just the product of color and line. I still accumulate and cultivate the ability of abstraction, because restoring the reality seen by the naked eye is simply to draw another copy of the material form, whereas the ability of abstraction is to keep the essence and remove other superfluous ones. So, the most challenging thing for abstraction is determining how and what essence to keep, and the poetic aspect is the first thing I consider.

Even the Chairs Want to Get Out, 1984, oil on canvas, 63×52cm, Beijing. Courtesy of Yan Li

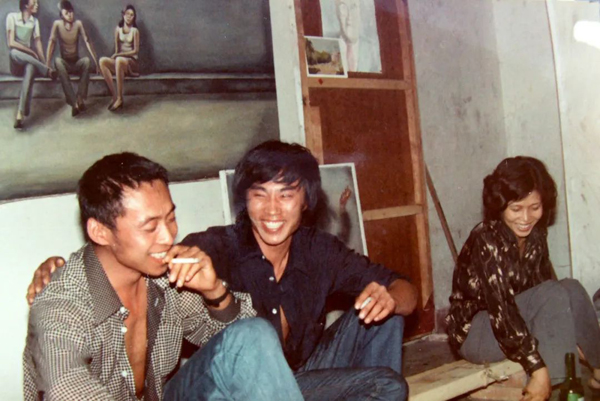

Hu Lingyuan: Do you join the Stars Art Group because the artist Huang Rui came over and selected your paintings? Looking back as a core member of Stars and Jintian, why were they founded?

Yan Li: He and I were both Jintian (Today) magazine’s participants and friends. I didn't invite him to pick my paintings because I began drawing less than three months ago. My friends merely knew that I wrote poetry and had no idea I painted. He came to my house to play and noticed a few paintings on the wall and asked who painted them. I told him I had just finished painting that, and he said your works are very original, you should join the Stars Art Group. At that time, he was looking for painters who could participate in the first exhibition of the Stars. His role is as a curator now.

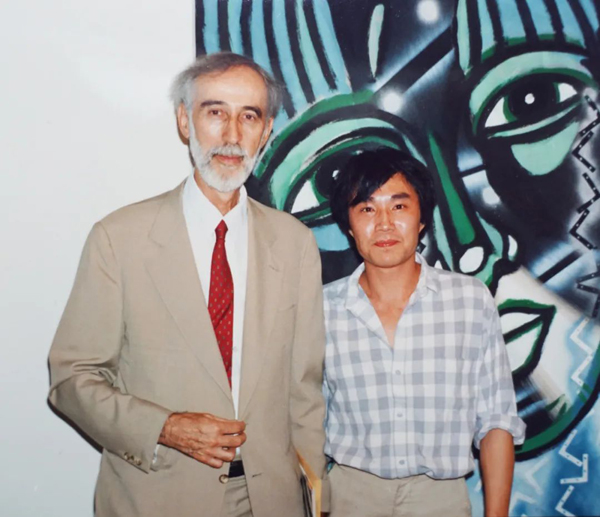

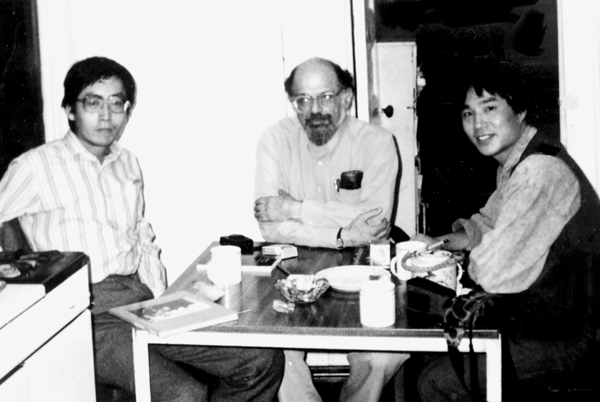

Zhang Wei, Yan Li and Li Shan at the home of Yang Yiping (the Star Art Group member), 1982. Courtesy of Yan Li

Yan Li: In my opinion, the Stars Art Group and Jintian are both vibrant salon forms in which everyone has their own ideas and thoughts, and they coexist in a pluralistic way so that they can absorb nutrients from each other. But if it is a strict group, it will form an interest group and a hierarchy of status within the group, which is not desirable in the field of literature and art. Therefore, the Stars Art Group and Jintian are a group of people of that era who want to speak their hearts out about life, who all want to be heard.

Hu Lingyuan: The First Stars Art Exhibition was held outside, and the Second Stars Art Exhibition was in an art museum. What happened then? Was the Stars Art Exhibition also contributed to your subsequent solo exhibition in Shanghai?

Yan Li: Back then, if you wanted to try out your personal voice, you could only do so in unofficial venues like the open air. After fighting for it, we were given the official venue of the National Art Museum of China once in 1980, and then when we applied again in 1981, it was never given to us again. I believe because the social impact of the Star Art Exhibition was too great. So, in 1984, I contacted my friends in Shanghai and organized my first solo exhibition in the name of young Beijing workers who love art. It was only because of the support of a group of old Shanghai painters (Yan Wenliang, Lu Yanshao, Wang Geyi, Ying Yeping, Li Yongsen, etc.) that everything went smoothly.

Drunken Moment, 1979, oil on canvas, the first Star Art Exhibition, Beijing. Image courtesy of Yan Li

Drunken Moment, 1979, oil on canvas, exhibited at Second Star Art Exhibition, Beijing. Courtesy of Yan Li

The Postponement of the first Star Art Exhibition in 1979 at the Beihai Park, Yuan Yunsheng with Star members: Li Shuang, Qu Leilei, Ma Desheng, Huang Rui, Yan Li, Bo Yun, and Zhong Acheng. Courtesy of Yan Li

Hu Lingyuan: Was there anyone who influenced your poetry?

Yan Li: My inspiration came from in ones and twos. When I was younger, I read a lot of literature books and some poems from Russia, England, and France that were circulated among young people at the time in a way of underground reading. But the true inspiration came from my inner thoughts and conscience because I was very young. Being young makes you curious and questioning about many things, which naturally inspires various forms of expression such as poetry and prose. Soulmates are those who understand your expression through your creation. We used to have “drawer literature,” which was finished writing and then we kept in our own drawer. Everyone wants to have their own secret when they are a teenager.

Dreaming of Myself, 1979, oil on canvas. Courtesy of Yan Li

Hu Lingyuan: Everything we encounter in life will eventually cause us to think. I remember you saying that “what is suppressed in life gradually becomes ore, and the poet is the one who mines it.” What is your perspective on history?

Ying Li: You can look at it from a personal perspective; everyone is a complete human being, with a self and the same seven emotions and six desires as others; reflecting on yourself will increase your understanding of the commonality of human good and evil; the difference is how much excessive desire you can restrain and how much good virtue you can promote. And our human resistance to aggression, even if we lose, drives us to fight the forces of evil, which is worthy to promote.

Life Has A Lot of Gambling Luck, 2021, acrylic on canvas, 76×100cm. Courtesy of Yan Li

“New York” 1996, Yan Li

Being in New York is equal to lengthening your lifespan.

The experience you get in a year

takes ten years in other places.

He who combines the experience of all human races is a person named New York.

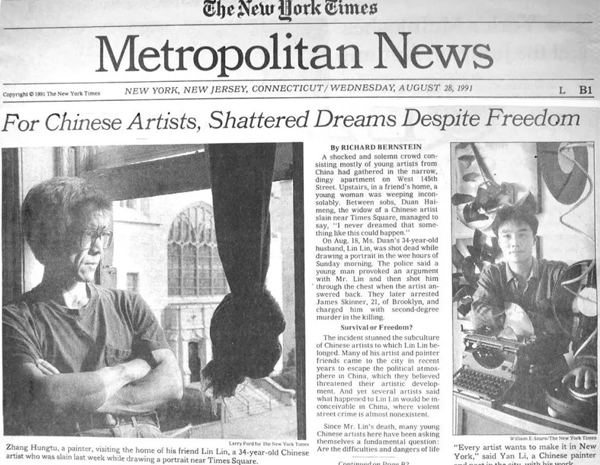

Hu Lingyuan: Why did you decide to come to the United States in the early 1990s? How did you solve the painting problems?

Yan Li: It had to be put in the context of the 1980s when people at home had the idea of wanting to go out and see, and since I was doing modern art, I was even more interested in seeing what kind of modernity was out there. After I left the country, I was fortunate enough to participate in several exhibitions and make some sales, so I quickly entered a more normal creation. At that time, I also applied to Pratt Institute of Art, and the head of the department looked at my work and said, “If you want to do art theory, then do a graduate program here, and after graduation, you can find a teaching position; and if you want to be an artist, your work proves that you already are.” So I went to Hunter College for a year and a half to study English, and Chen Yifei, who came out a few years before me, also studied English there. Later, I spent a year at the Art Students League of New York studying printmaking techniques, and I was Mu Xin’s classmate for six months.

Yan Li's painting “The Blues” hanging at the Prudential Disco Club, New York, 1988. Courtesy of Yan Li

Hu Lingyuan: Is there anything noteworthy? How do you stay alive?

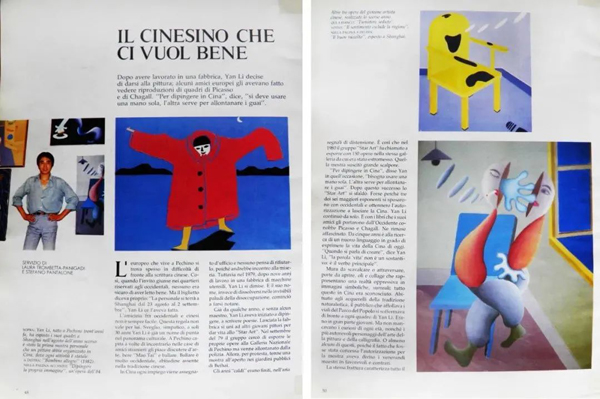

Yan Li: There are numerous things that come to my mind. In 1986, I was studying English, and many of my classmates were from non-English speaking countries, so when I introduced myself in class, I said I painted and wrote poems. Later, my English teacher challenged me to write some poems in English, which I did, but I thought it was very childish, whereas he thought it was good and recited it for me in class. Another Italian student asked if she could see my paintings, and after a few days, I brought her some paintings and she said she liked them a lot and ask if I could sell them to her. When I asked her why she bought them, she said she saw my work in an Italian magazine a few months ago. Soon after I asked her to find the magazine, I found 6 pages about my paintings, which were probably reported by some western journalists who had previously been in China or published by foreign students after they returned to China because it was not long after the opening and foreign countries were very interested in China. As for survival, besides selling paintings, I worked odd jobs in New York, the longest of which was opening a “360-degree photography studio” with a friend, which is commonly known as a photo studio, and running it for 5 years.

Reported by Italian Art Magazine. Courtesy of Yan Li

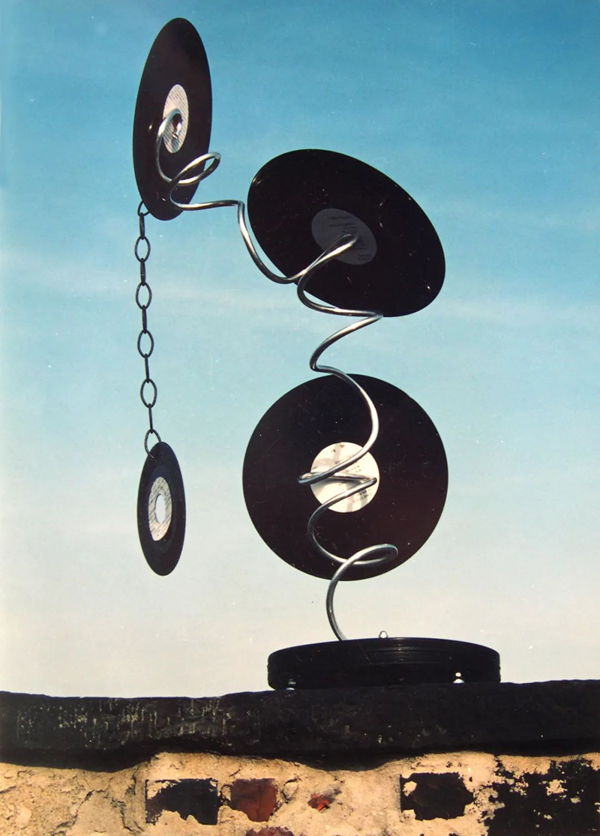

Hu Lingyuan: Your record series in New York has lasted to this day. Why did you choose records?

Yan Li: After cassette tape became popular, vinyl records were gradually phased out. When I arrived in New York in May 1985, it had already been extensively phased out, so it was easy to find vinyl records that had been discarded as garbage, but some people surely would collect some rare versions. I discovered that collage with this material worked well because its black has a texture more than black pigment. I tried it in the second half of 1985 and got pretty good at it because, if it was a painting with a musical theme, using it up could help the viewer associate with music more easily. So, depending on the need for black, I would still use it in the picture often for the next thirty years or so. I've also created sculptures out of vinyl records, which have another different flavor.

Hero and Cage, 2020, acrylic, and vinyl on canvas, 28×22cm. Courtesy of Yan Li

Record Sculpture, 1986, sculpture, Courtesy of Yan Li

Hu Lingyuan: Were there any collaborations with other artists during this period?

Yan Li: We took part in several group exhibitions in New York galleries. Seven or eight of us were the first mainland artists to exhibit in the United States. In 1986, for the first time, Americans were able to see the types of modern paintings created by Chinese artists, and the exhibition toured to Vassar College in upstate New York, the City Gallery in New York, and other locations. In addition, Chen Danqing, Ai Weiwei, Yuan Yansheng, and I organized the first group exhibition of pioneering art with the name of mainland China curated by Taiwanese painter Yang Zhihong in 1987. We all went through different phases of exploration and shared many of the same experiences. As for Chinese artists who went abroad, some discovered their other talents soon after they arrived and moved on to other areas.

Group painting exhibition at St. Lawrence University in 1986. Courtesy of Yan Li

Hu Lingyuan: Was the photo you took with artist Ai Weiwei at the World Trade Center in New York random or deliberate? What does it mean to you?

Yan Li: This was a random event. It happened in summer and there were very few people in the square, so I proposed taking a picture here and did so in under one minute with my camera. In retrospect, this belongs to the category of conceptual or performance art. We had just left China and were eager for new forms to express ourselves, or something that Westerners had done that the Chinese had not yet done, and what we felt at the time was that we wanted to be naked in a public place to challenge our own courage. Despite the randomness of our actions, the power to take this step should come from the pursuit of self-expression and from the breakthrough of forms.

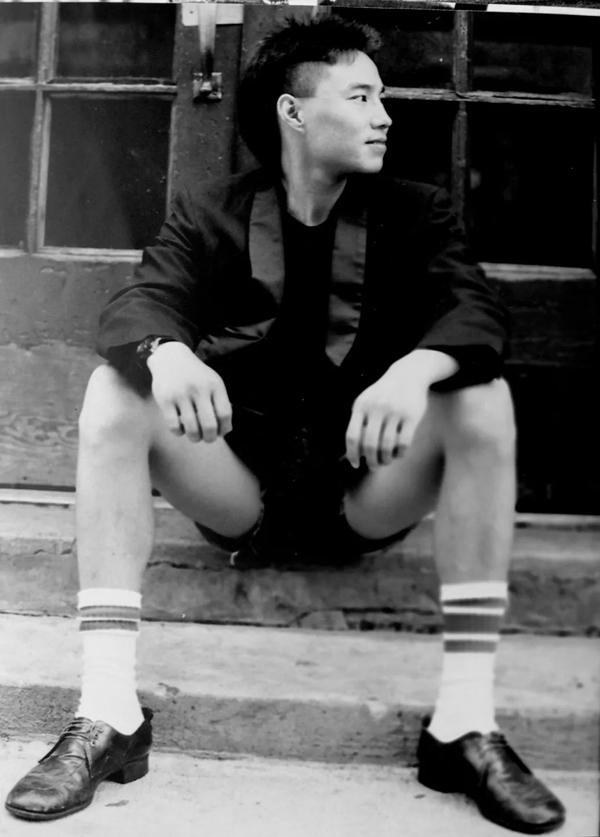

Yan Li in East Village, New York, 1985. Photo: Ai Weiwei. Courtesy of Yan Li

Hu Lingyuan: After 9/11, you wrote the novel “Encounter with 9/11” and painted the “Combustion” series. Can you talk about this?

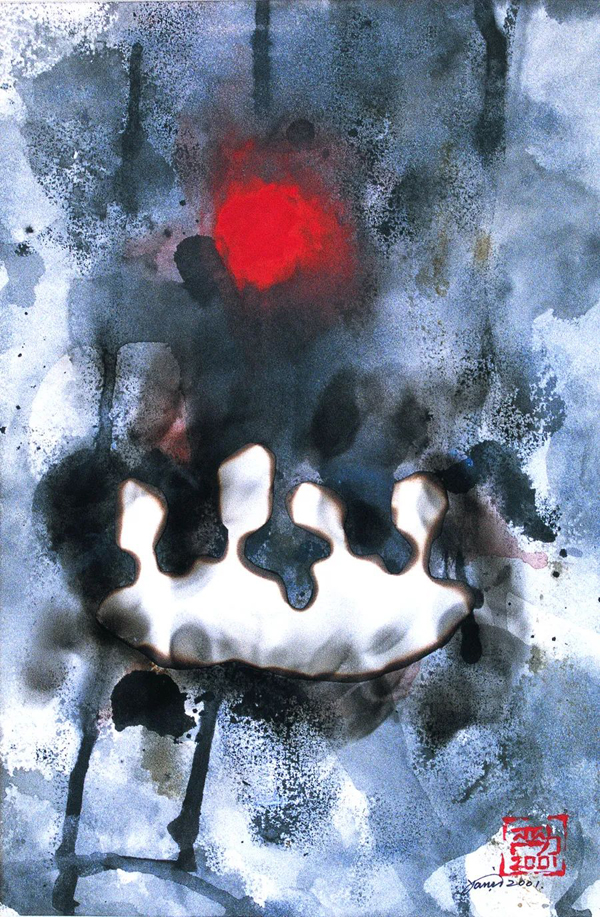

Yan Li: 9/11 was a great shock to the whole human race, and I was in New York at the time, so I felt compelled to write something. To gather more social reactions, I ran from New York in the east to Los Angeles in the west shortly after 9/11, stopping at several places along the way to record and observe for about two weeks. When I back to New York, I wrote this novel, which is a combination of realism and non-realism. I am satisfied with it and since it was in Chinese, I gave it to Jia Zongpei, the editor at the Shanghai Literature and Art Publishing House, who agreed and published “Encounters with 9/11” a year later, in 2002. “Combustion”, a series of paintings on paper, was exhibited in galleries in New York and at the University of lowa Stanley Museum of Art. I put together a collage using ink, acrylic, and some burned paper to give the impression of suffocation after the explosion. I also have a poem about 9/11:

Memorial

On the day of September 11, 2001

I saw a footage of someone jumping off

The World Trade Center

On the TV screen

This scene replayed in my mind

Over and over for many following days

Repeatedly

Replaying

And I wish continually there were water below

A swim pool

A diving competition

Several times

I even felt the water splash

Not long ago

The water really splashed

And damped my clothes

Because I suddenly grasped

A way to ferry him into heaven

Through my inner world

2001

Combustion Series, 2001-2002, acrylic, ink, fire, glue on paper, 40×32cm. Courtesy of Yan Li

Combustion Series, 2001-2002, acrylic, ink, fire, glue on paper, 32×40cm. Courtesy of Yan Li

Hu Lingyuan: Tell us about your poetry group “First Line”.

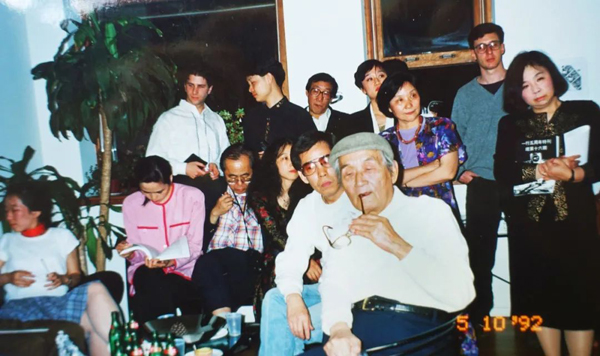

Yan Li: “First Line”, a poets and artists group, was the first overseas Chinese poetry publication that I advocated for in New York in early 1987. We had about twenty to thirty people at the time, and we planned to publish an issue every three months, with each person contributing one day's salary to the publication costs each quarter. We had many core members: Wang Yu, Zhang Er, Wang Ping, Li Fei, Cheng Buqui, Qin Song, Hao Yimin, Peng Bangzhen, Tang Degang, as well as American poets Ginsberg and Swartz, artists Ai Weiwei, Zhang Wei, Shen Chen, sinologist Si Zhongda, and more. On May 10, 1987, we launched “First Line,” a quarterly poetry and art journal that primarily published modern poetry from mainland China but also works from overseas and Taiwan and Hong Kong, as well as works by famous Western poets translated into Chinese, and paintings and illustrations by artists in each issue. We also received a lot of help from Chinese industrialists Chen Xianzhong and Sophie Luo, whose printing house gave us a lot of discounts every time they printed the magazine. This couple has been involved in many activities in New York, including lawsuits claims against the Japanese government, comfort women, and the Diaoyu Islands. They organized a painting exhibition to commemorate the anniversary of the Nanjing Massacre in the 1980s, and many Chinese artists in New York, including myself, participated in the creation of the paintings. For a few years, they also printed New York subway newspapers and gave them to the homeless in New York to sell in the subway for free, with all the proceeds going to the homeless. In addition, Cheng Buqui, head of the East Asia Department at Pace University in New York, is a Chinese poet who writes poetry. He thought that “First Line” was a record of Chinese folk poetry, so he helped us ship eight boxes of poetry books (400 books in total) to China for free with every issue.

From left to right: Li Fei, Qin Song, Bei Dao, Gu Cheng, Yan Li, Wang Yu, Zhang Langlang, Bei Ling, Shen Chen, New York, 1988. Courtesy of Yan Li

Bei Dao, Ginsberg, Yan Li, at Ginsberg's home in New York's East Village, 1988. Courtesy of Yan Li

First ine's third anniversary in New York, 1990 recital. Courtesy of Yan Li

Hu Lingyuan: The philosophy of the “First Line” is that Poetry, lines written one after another; human being, being human by one deed after another. So, you place more emphasis on the poems’ quality.

Yan Li: Yes, the nutrition is in the work, not in the name of the author. We should focus efforts on our work rather than on spreading and branding our name.

“A Poem to Mothers” 2020, Yan Li

In these turbulent times

the day you said goodbye

came suddenly

But you still reside inside me

continuing to give blessings as I endlessly surf

Hu Lingyuan: Return of Mother Tongue (1995) was awarded the Best Long Story Award along with Zhang Wei's “Family” and Mo Yan's “Breasts and Butts.” The title of the book is very intriguing; why is it called that?

Yan Li: After leaving Beijing for New York, I went back to China for the first time at the end of 1993 and again in 1994. I had a close reacquaintance with China after eight or nine-year absence, so I wrote “Return of Mother Tongue” to write about some of the events in New York and after I returned to China, that is, I created this novel in work with my mother tongue, with which I lived in New York for ten years.

Hu Lingyuan: You wrote in “Zhang San, who studied abroad” (2003) that he is pursuing an enviable Ph.D. degree in the Department of Contemplation at a foreign university. What does home mean to you? Do you still go back often?

Yan Li: After 2000, I often returned to my home country at least once a year for three or four months at a time. The secular concept of home is made up of relatives, but with social experience and experience, I found that being with good friends also feels like with family, because they share the same life philosophy and are even closer. Some of my American friends felt like family to me as well. Speaking of coming home, I wrote a poem at the turn of this century:

Back Home

Back home

He shed his shoulders too and put them into a closet

The loosened springs

Sunk into their own couch

Back home

He returned the dream that has parted from pillows for years

Back to his sleep

Back home

His face broke the rigid portrait

Smiling from ear to ear

Back home

Calluses still were on his worn feet

Yet his footsteps started to transform into a tranquil melody

Back home, back home finally

He saw all the furniture

Mew softer than a tamed cat

2000

Smell the Body, 2020, acrylic on canvas, 50×66cm. Courtesy of Yan Li

Hu Lingyuan: Mother is the first person who comes to our mind when we think of home. The death of your mother must have been a big shock to you. What was her most profound influence on you?

Yan Li: I was prepared for this shock because of the natural human lifespan. It was only a few days from the time she was admitted to the hospital until she died, and with the COVID-19, I simply couldn't get back to Beijing in time. My mother had never painted anything before, but after she retired, she suddenly learned Chinese ink painting and painted for more than 20 years, as well as participated in many exhibitions for the elderly. Then I realized that she had such an original artistic gene in her body, which, combined with seeing too much of my grandfather's collection as a child, influenced me to become an artist. Her friendliness was another factor that impacted me. When my friends came to visit me at the time, she would take the initiative to suggest that I can invite my friend to eat together whenever it was dinner time, and the most popular dish was dumplings because she was from Shandong and was born in Beijing. So, in New York, I occasionally entertained my friends with hand-rolled dumplings.

Music Dumplings, 1988, sculpture. Courtesy of Yan Li

The First Time to Dine with 21st Century

Sit down!

I am over flattered by the consensual seat

Fate calms me down with lucky coincidence

In an unknown vision

a few artistic snowflakes start to melt

I exclaim with happiness:

neither postponement nor advance

It fits the transition from winter to spring

It fits the distance from first contact to love

But it also fits this farewell

Don’t wish!

The hand that reaches out from the background of history

pulls me back into the frame where I was registered:

Please keep the relationship with the old photo

Please continue to wear out the previous exposure

But the heavier weight makes me sit here

sitting down to endure the gradually-computerized appetite

sitting down to receive the nutrition-following-digital emails

This is the download of the new century’s first emotion software

I call the waiter over,

"Bring the bill.

I need to catch the 9:00 p.m. shuttle to Mars.”

2001.1

Note:

All poems and First Line’s concept are translated by Anna Yin.

Yan Li (B1954.Beijing.China).He is a painter and a poet. He move to New York USA on 1985. In 1987, he founded the "First line" poetry journal in New York, and was editor in chief (ceased publication in 2000) and reissued in June 2020 as semi-annual magazine. He became chairman of the Flushing Poetry Festival in New York from 2018.And the chairman of the Overseas Chinese Writers'Pen Association in New York.