The scene is framed at the top of the building, and jarring sounds appear one after another. A small circular sculpture (possibly a circular stage) then shows up in the next framed shot, with natural light and shadow subsequent pouring in slowly as a tidal surge, until they cover the entire ground. The camera switches again to another part of the square, where natural light and shadow begin to fade with the passing of time. Then, Martha Graham’s text appears on the screen in a ghostly and cold atmosphere. The circular stage emerges and “For a Dance Never Choreographed” comes to its climax in its center.

For a Dance Never Choreographed. Photo by Stefano Croci. Courtesy of the artist

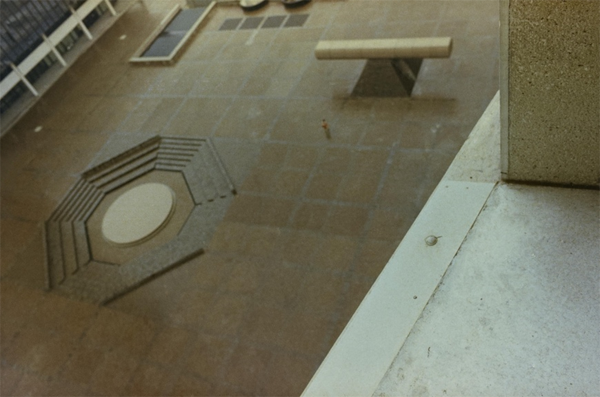

“For a Dance Never Choreographed”, as the film’s title suggests, is a dance drama staged in the Piazza, Fiere di Bologna without the physical presence of dancers. The piazza, designed by Isamu Noguchi (commissioned by Japanese architect Kenzo Tange), provides a suitable breeding ground for the dance drama, allowing it to move out of human involvement and direction into a dance sequence of time and space, with natural light and shadow acting as the only dancing elements visible in the film. Italian choreographer Luca Veggetti as the film’s director also distills the possibilities and spatialization of the interior of Piazza, Fiere di Bologna. This Piazza is primarily comprised of two main elements: a sculpture known as the gate by Isamu Noguchi - a giant granite pillar with sloping sides placed on top of a truncated pyramid - and a sunken octagonal amphitheater that also serves as the main performance venue for “For a Dance Never Choreographed”. This sunken theater has a total of eight inclined surfaces, which are formally divided into two groups (four each), with one group of the inclined surface having three rows of stepped seating and the other group having six rows. They are separated and crossed, encircling the gray and white circular stage raised in the center of the octagonal amphitheater. Viewed from above, the octagonal amphitheater is shaped like the ancient Chinese eight trigrams (also in the shape of a square eight). According to “I Ching”, eight trigrams are derived from the ancient Chinese concept of the fundamental cosmogenesis, the relationship between earth’s rotation (yin and yang) corresponding to the sun and moon, and the interplay of agricultural society and philosophy of life. The “trigrams” were an ancient way of measuring the movement of the sun, determining the change of seasons and recording the patterns of labor. From this cultural perspective, the Piazza reflects the designer’s Eastern philosophical thinking and the notion of integration with the rhythms and forms of all things in architecture and environment. Similarly, Luca Veggetti’s film also embodies the same concept.’

Isamu Noguchi, Piazza, Fiere di Bologna (1979–83), Bologna, Italy. Photograph c. 1980s. The Noguchi Museum Archives, 12443. The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, NY / Artists Rights Society

Although I have never been to the Piazza and its octagonal amphitheater, and have no way to perceive its exact size, the surreal temperature of the film allowed me to envision Luca Veggetti standing in the middle of the stage or sitting alone somewhere. He is constantly surveying, examining, and then conceiving how to respond to this space with an almost ethereal and remote dance. The way I recall, Luca Veggetti’s dance always has a minimalist and serious divine quality. The New Yorker commented that his dances “tend to be sculptural, cerebral, and spare.” Yet in this Piazza, which he has known since childhood, he firstly abandoned the artificial form of dance, and instead captured the imagination and vitality of the Piazza, both inside and outside, through the form of a film documentary. In the artist’s statement, he writes, “I have known the Piazza, Fiere di Bologna since I was a child, and it has been for me an instrument of imaginative birth: a gigantic stage, a set, an archipelago of interrelated spaces and sculptural objects of metaphysical quality.”

For a Dance Never Choreographed. Photo by Stefano Croci. Courtesy of the artist

The Tempest Songbook - Gotham Chamber Opera/ Martha Graham Dance Company, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015. Photo: Richard Termine. Courtesy of the artist

In this archipelago, the natural dance performance completely manifests the multidimensional and hidden space of the Piazza, and its creativity as a public area. The Piazza thus reveals the most ideal dramatic effects of its creator. Sound, rhythm, text and image are significant elements of the film, collaborating to inspire one’s imagination to a non-physical space that transcends the human dimension. As the “trigrams” I mentioned earlier are a means of observing the changes of the sun, it seems that Luca Veggetti’s film does the same through the natural light and shadow’s emerging and fading, as if we are immersed in the emptiest surface of the earth to watch the footsteps of time transforming into the shifting of light and shadow in accordance with the laws of nature. In the East Rising and West Setting, Luca Veggetti contributes an aesthetic observation of the Piazza demonstrating Isamu Noguchi’s interpretation of its original properties—it is not only a public space for human beings to leap for, but also a place for all-natural life forms to be imagined and where to touch a sense of emptiness. In an essay written for this film, senior curator Dakin Hart quotes Noguchi writing in his autobiography: ‘There is a difference between actual cubic feet of space and the additional space that the imagination supplies. One is measure, the other an awareness of the void—of our existence in this passing world.’

Tanto quanto dura il soffio: per Bruno Munari - Setagaya Art Museum, Tokyo, 2018. Photo by Teppei Hori. Courtesy of the artist

In the midst of the changing situation and physical alterations caused by the pandemic, For a Dance Never Choreographed can still be regarded as Luca Veggetti’s instinctive response to it, even if it is not hard to envision the desolate reality reflected in the dance and the Piazza in any given context and situation. His entire imagination, born from within, is also a lament and a prayer for the mourn of reality.

Born in Bologna, Italy in 1963 and trained at La Scala in Milan, Veggetti began his career as a choreographer and stage director in 1990. Turning his interests toward contemporary music and experimental forms, he has collaborated with some of today’s most important ensembles and composers. His work has been produced and presented by leading theaters, companies, and museums around the world including The Drawing Center, Works & Process at the Guggenheim, The Martha Graham Dance Company, BAM, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, La Cité de la Musique in Paris and Suntory Hall in Tokyo. Notable productions include Iannis Xenakis’ Oresteia at the Miller Theater in co-production with the Guggenheim’s Works & Process, Kaija Saariaho’s Maa at La Cite’ de la Musique in Paris, NOTATIONOTATIONS for the Drawing Center in collaboration with artist Susan Hefuna, the world premiere of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Vivo e Coscienza at Mittelfest in Italy, Toshio Hosokawa’s operas Hanjo at Tokyo’s Suntory Hall, The Raven for Gotham Chamber Opera at the first New York Philharmonic New Music Biennial and Vision of Lear in Hiroshima, Kaija Saariaho’s operatic work The Tempest Songbook for Gotham Chamber Opera with the Martha Graham Dance Company at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Scenario, a performance/video installation conceived for the spaces of MART in Italy. Recent productions include Left-Right-Left, a co-production by the Japan Society in New York and the Yokohama Noh Theater, Iannis Xenakis' Kraanerg for the Teatro Comunale in Bologna, Watermill, a new vision of Jerome Robbins' iconic theater piece for the Next Wave Festival at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, Infinito Nero, an operatic work by Salvatore Sciarrino in Bologna, Anatomy of the Dream: Shojo Midare, a performance of a Noh play conceived and directed for the spaces of the Setagaya Art Museum in Tokyo.